on communes

communing and possessions

To reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I. We are no longer ourselves. Each will know his own. We have been aided, inspired, multiplied.

To be fully a part of the crowd and at the same time completely outside it, removed from it: to be on the edge, to take a walk like Virginia Woolf (never again will I say, “I am this, I am that”).

Freud tried to approach crowd phenomena from the point of view of the unconscious, but he did not see clearly, he did not see that the unconscious itself was fundamentally a crowd.

— Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (trans. Brian Massumi), A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

Why read notes? We understand them to be by nature premature, unrefined, raw, private. Yet when a revered author’s notebooks are published posthumously we rush to get a copy and glean what telling details we can from their unauthorized pages. How revealing the notebook is depends mainly on the author, who may or may not have kept notes with publication in mind, usually after death, but sometimes before. Who may have considered the notebook’s purpose to be entirely personal, too obscure or cryptic or banal to be of use to the public. (Can a notebook be purely private? Or is it necessarily attached to collective endeavor, and therefore held in common; a conduit between self and world; between works in progress and other oeuvres; between past and present, and future?)

And then, why publish notes at all? Aren’t they a bit beside the point? The point being the artwork to which the notes are always in service. To which the artist is always in service. Do notebooks then represent their keepers? Divulging interiors despite containing, mostly, sketches of exteriors. Who said what where and when. Familiar strangers on the metro. Qualities of light or the emptiness of chairs or the way the dog settled herself on the rug. Such details feel personal, even as they are essentially communal events. (Anyone else could have noticed, or did. Recognition flickers in the reader, despite physical and temporal removes.) We write them down in part so we can return later, and dredge our memories for inner responses to outer situations. Reading someone else’s notes can be an empathic exercise, or a voyeuristic one, or a kind of possession. The notebook is that liminal zone where we commune with other selves.

When Virginia Woolf was thirteen, she wrote, “I believe after all that human beings would find it very difficult to exist together if they knew each other.”1

— Panthea Reid, Art and Affection: A Life of Virginia Woolf

In his 1953 Preface to A Writer’s Diary, Leonard Woolf is at pains to justify publishing selections from his dead wife’s diaries. He concedes the fundamental mistake in publishing extracts, whose “omissions almost always distort or conceal the true character of the diarist or letter-writer and produce spiritually what an Academy picture does materially, smoothing out the wrinkles, warts, frowns, and asperities.” The diary cannot be published in full, he says, because it is “too personal”—a concern for the privacy not of the deceased author, but of those still living whom she mentions in its pages. He publishes it only because, he hedges, Virginia Woolf “was, I think, a serious artist and all her books are serious works of art,” citing the commentary of Professor Bernard Blackstone to support this estimation. A Writer’s Diary depends on such commentary for its value and interest to readers, says Woolf, because the author used her diary “in a very individual way as a writer and artist. In it she communed with herself.”

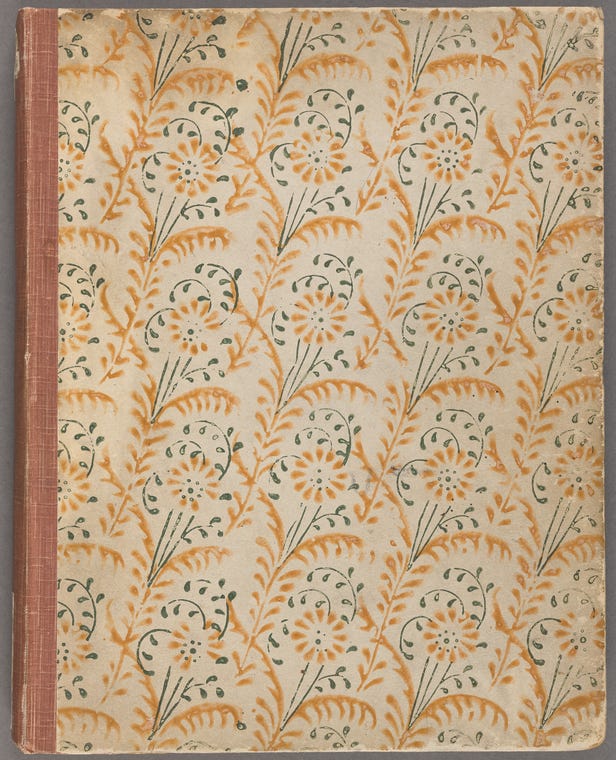

The widower describes the notebooks his wife used both for her novels and the many volumes of her diary in some detail: blank sheets of roughly letter size paper (“technically large post quarto”) bound with covers made from the same patterned Italian papers, “of which she was very fond,” that they used to bind the poetry books they published together as The Hogarth Press2. Woolf sums up this spare account with a tally of the 26 volumes of diary left at her death, in hand printed notebooks, written, he emphasizes, “in her own hand.” Around the stack of handwritten journals settles an aura of personhood.

We have no title-deeds to house or lands; Owners and occupants of earlier dates From graves forgotten stretch their dusty hands, And hold in mortmain still their old estates.— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Haunted Houses”

Mary Shelley knew her mother, the author and early feminist thinker Mary Wollstonecraft, who died eleven days after a complicated childbirth, solely through her writing. Her father, the author William Godwin, whose necromantic Essay on Sepulchres argued for memorializing the burial sites of eminent persons and encouraged necro-tourism, brought Mary at a young age to the churchyard where her mother was interred.3 The cemetery had been the site of the Godwins’ wedding just five months before her death; it would eventually become the setting of their daughter’s love affair with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and where she is believed to have lost her virginity to him. She would spend many hours at the grave reading her mother’s books, having apparently learned to write her given name by tracing the headstone’s engraving. Mary sought communion with her dead mother through her writing, a resurrection from remnants akin to the undead monster she would later create in her most famous novel.

Her adult life would likewise be marked by deaths: the suicides, two months apart, of her half-sister and Shelley’s first wife; the tragic early losses of three of her four children, one to premature birth and two to illness, as well as a miscarriage that nearly caused her own death; Shelley’s sudden death in a drowning accident at sea. Mary kept a journal throughout adulthood, and she also kept a joint journal with Shelley during their travels together after their elopement. Her early journal entries are reserved, only briefly recording her activities, travel and reading logs. After Shelley’s death, the entries lengthen, growing into more confessional and emotive reflections on grief and solitude. In some Mary writes as if speaking directly to Shelley.

Wollstonecraft’s books acted as a kind of surrogate mother, serving after her death as model and guide for her daughter. One of these was Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a frank biography written by her grieving husband. He justifies its publication with utilitarian purpose in his Preface, linking his late wife’s experiences to the common good: “There are not many individuals with whose character the public welfare and improvement are more intimately connected.” Against the publisher’s advice, Godwin spared no sensitive details from his wife’s life and failed to conceal the identities of others involved. The text caused a scandal on its publication in January 1798, as it exposed Wollstonecraft’s love affairs, an illegitimate first child, an intimate female friendship, failed suicide attempts, and the agonizing circumstances of her postpartum death. Despite a revised second edition published that summer, irrevocable damage was done to the reputations of Wollstonecraft and those named in the biography, as well as to Godwin, whom the poet Robert Southey denounced for “want of all feeling in stripping his dead wife naked.” A bitter Godwin would fault his friend William Hazlitt over a decade later for including too many of his own offhand comments and careless jokes in Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft, complaining of indiscreet biographers who “draw out to view the privacies of firesides.”

The more the critical reason dominates, the more impoverished life becomes; but the more of the unconscious, and the more of myth we are capable of making conscious, the more of life we integrate. Overvalued reason has this in common with political absolutism: under its dominion the individual is pauperized.

— Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections

In her reclusive later period following a bout of consumption and a painful eye affliction, Emily Dickinson rarely left her family home in Amherst; she continued writing poetry, drafting manuscripts on scraps of paper, and had several respected visitors at the house. One visitor was the radical abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a pen pal to whom Dickinson remarked on their first meeting in 1870: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?” Higginson would read a selection of poems by “unknown poetesses” at the New England Woman’s Club in Boston five years later; one of these anonymous authors is believed to have been Emily Dickinson. Founded in 1868 by and for women, the club allowed some male members, guest lecturers, and attendees. Among early male supporters of the club were Ralph Waldo Emerson and Bronson Alcott.

Your thoughts don’t have words every day They come a single time Like signal esoteric sips Of the communion Wine— Emily Dickinson

Bronson Alcott co-founded the utopian agrarian commune Fruitlands with Charles Lane, who purchased the 90 acre Wyman farm in Harvard for that purpose in May 1843. (Alcott having recently gone broke following the failure of his experimental Temple School in Boston. His plans for a farm community began around the time of his controversial school’s closure.) Though never financially solvent before the literary success of his daughter, Alcott was yet a highly regarded and influential educator, transcendentalist, abolitionist, and reformer. With the help of Ralph Waldo Emerson, in 1842 he visited his most enthusiastic group of supporters at the Alcott House—an English spiritual community and progressive school on Ham Common in Surrey founded in 1838 by the socialist reformer and mystic James Pierrepont Greaves and a cohort of wealthy followers that included Charles Lane. In pursuit of spiritual purification through healthy living, Greaves’ community followed a stringent, mostly raw vegan diet, rejected contemporary styles of dress in favor of plain clothing and untrimmed hair and beards, and eschewed luxuries like caffeine and hot bathing water. Lane and Alcott would apply similar principles of asceticism and veganism at Fruitlands, where they moved together with their families in June 1843.

Here life is simply sorted out into its main elements. Each man and woman has his work; each works for the health or happiness of others. And here, in this little community, characters become part of the common stock; the eccentricities of the clergyman are known; the great ladies' defects of temper; the blacksmith's feud with the milkman, and the loves and matings of the boys and girls. Here life has cut the same grooves for centuries; customs have arisen; legends have attached themselves to hilltops and solitary trees, and the village has its history, its festivals, and its rivalries.

— Virginia Woolf, “On Not Knowing Greek”

Though well resourced, Alcott House was not long lived and shuttered in 1848. It nevertheless outlived Fruitlands, which lasted just seven months before failing in its first winter. Alcott’s daughter Louisa satirized the family farm experiment in “Transcendental Wild Oats,” which would be published along with excerpts from the diary she kept at the farm in Clara Endicott’s 1915 history Bronson Alcott’s Fruitlands. Both satire and diary offer accounts of a gendered division of labor, with the male stewards of the commune primarily spending their days in philosophical conversation while the female family members spend the majority of their time doing the hard work of subsistence. “Anna and I did the work,” begins an entry on Friday November 2nd. “In the evening Mr. Lane asked us, “What is man?” These were our answers: A human being; an animal with a mind; a creature; a body; a soul and a mind. After a long talk we went to bed very tired.” An adult Louisa adds her comment in a later footnote to this entry: “(No wonder, after doing the work and worrying their little wits with such lessons.—L. M. A.)”4 The author would revisit themes of female labor and exploitation, as well as collaboration and women’s support networks, in her semi-autobiographical allegorical novel, Work: A Story of Experience.

The world was not ready for Utopia yet, and those who attempted to found it only got laughed at for their pains. In other days, men could sell all and give to the poor, lead lives devoted to holiness and high thought, and, after the persecution was over, find themselves honored as saints or martyrs. But in modern times these things are out of fashion. To live for one’s principles, at all costs, is a dangerous speculation; and the failure of an ideal, no matter how humane and noble, is harder for the world to forgive and forget than bank robbery or the grand swindles of corrupt politicians.

— Louisa May Alcott, “Transcendental Wild Oats”

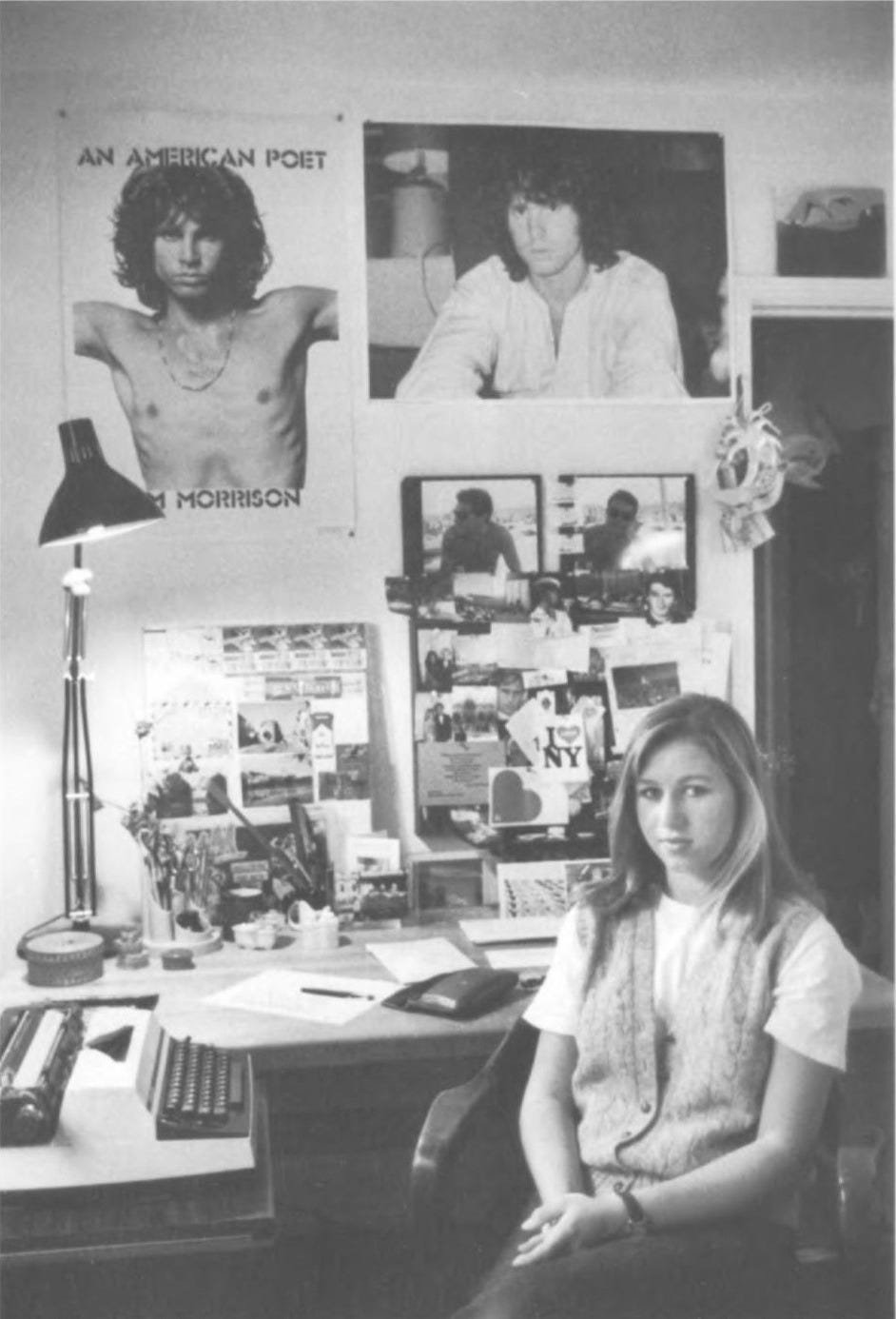

“Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point.” Joan Didion arrives at this motive for note taking in her 1966 essay, “On Keeping a Notebook.” First she entertains, then disillusions us of numerous false motives: utility, “to have an accurate factual record,” virtuous thrift, “an instinct for reality,” interest in other people, “a structural conceit for binding together a series of graceful pensées,” relevance. She admits her folly in imagining her notes are actually about other people, and attributes such posturing to social expectations of selflessness. “But our notebooks give us away,” she confesses, “for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I.’” Even when she records the activities of other people in her notebooks, she insists, these observations remain wholly subjective, private, “bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker. And sometimes even the maker has difficulty with the meaning.” Anyway, she reminds us, making meaning is beside the point, which is only to “keep in touch” with our past selves. “And we are all on our own when it comes to keeping those lines open to ourselves: your notebook will never help me, nor mine you.” This might have been a natural place to end the essay, but Didion instead closes on a memory of watching a blonde Californian woman she’d seen poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel several years earlier, exiting Saks Fifth Avenue in a last season mink coat, looking old and “irrevocably tired.” The sight chills her deeply, a midtown memento mori:

For a while after that I did not like to look in the mirror, and my eyes would skim the newspapers and pick out only the deaths, the cancer victims, the premature coronaries, the suicides, and I stopped riding the Lexington Avenue IRT because I noticed for the first time that all the strangers I had seen for years—the man with the seeing-eye dog, the spinster who read the classified pages every day, the fat girl who always got off with me at Grand Central—looked older than they once had.

Notes to John is probably not the type of notebook Didion is writing about in 1966. Discovered by her literary trustees after her death and published last month, the unedited diary is addressed to Didion’s husband and meticulously records the author’s private therapy sessions, which focused particularly on her close but troubled relationship with their adopted daughter, Quintana. (Both husband and daughter predeceased the author by almost two decades.) Without explicit instructions, we can’t know Didion’s intention in leaving the journal in a drawer for the trustees of her estate to find. Certainly she must have expected it to be preserved, cataloged and archived with the rest of her and her husband’s papers at the New York Public Library. She must have also considered the likelihood of posthumous publication, which she apparently chose not to instruct against. A pronounced ambiguity, for one of the most exacting, controlled, famous authors in American literature.

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

This quote appears in “The Hyde Park Gate News,” a family newsletter written mostly by Virginia.

Named for Hogarth House, the couple’s home in Richmond where they began printing on a small hand press in their dining room.

Paul Westover develops these ideas in his study of necro-tourism, literary pilgrimage and preoccupation with the dead during the Romantic period in Necromanticism: Traveling to Meet the Dead, 1750-1860.

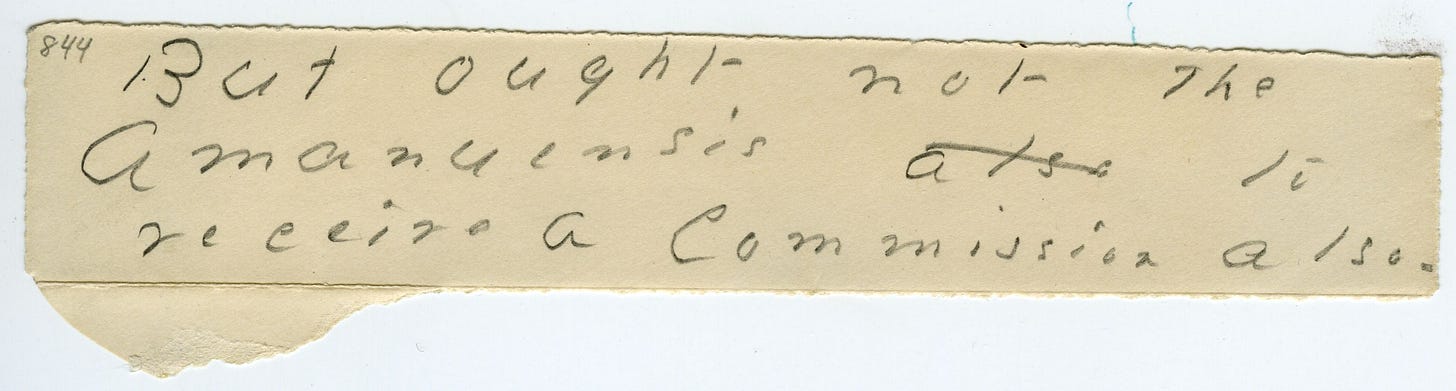

Abigail May Alcott frequently read her daughter’s diaries, and would leave her notes of encouragement and guidance, such as this one written in the Fruitlands diary: “Dear Louey,—Your handwriting improves very fast. Take pains and do not be in a hurry. I like to have you make observations about our conversations and your own thoughts. It helps you to express them and to understand your little self. Remember, dear girl, that a diary should be an epitome of your life. May it be a record of pure thought and good actions, then you will indeed be the precious child of your loving mother.” Louisa kept extensive journals and letters throughout her life that she later revised and edited, though she never intended to publish them.