on scales

the balances of notework

50% of all subscription proceeds in 2025 will be donated to wildfire relief and immigrants’ rights groups

I sometimes tell very young writers that to become a writer is to have homework due for the rest of your life.

—Alice McDermott

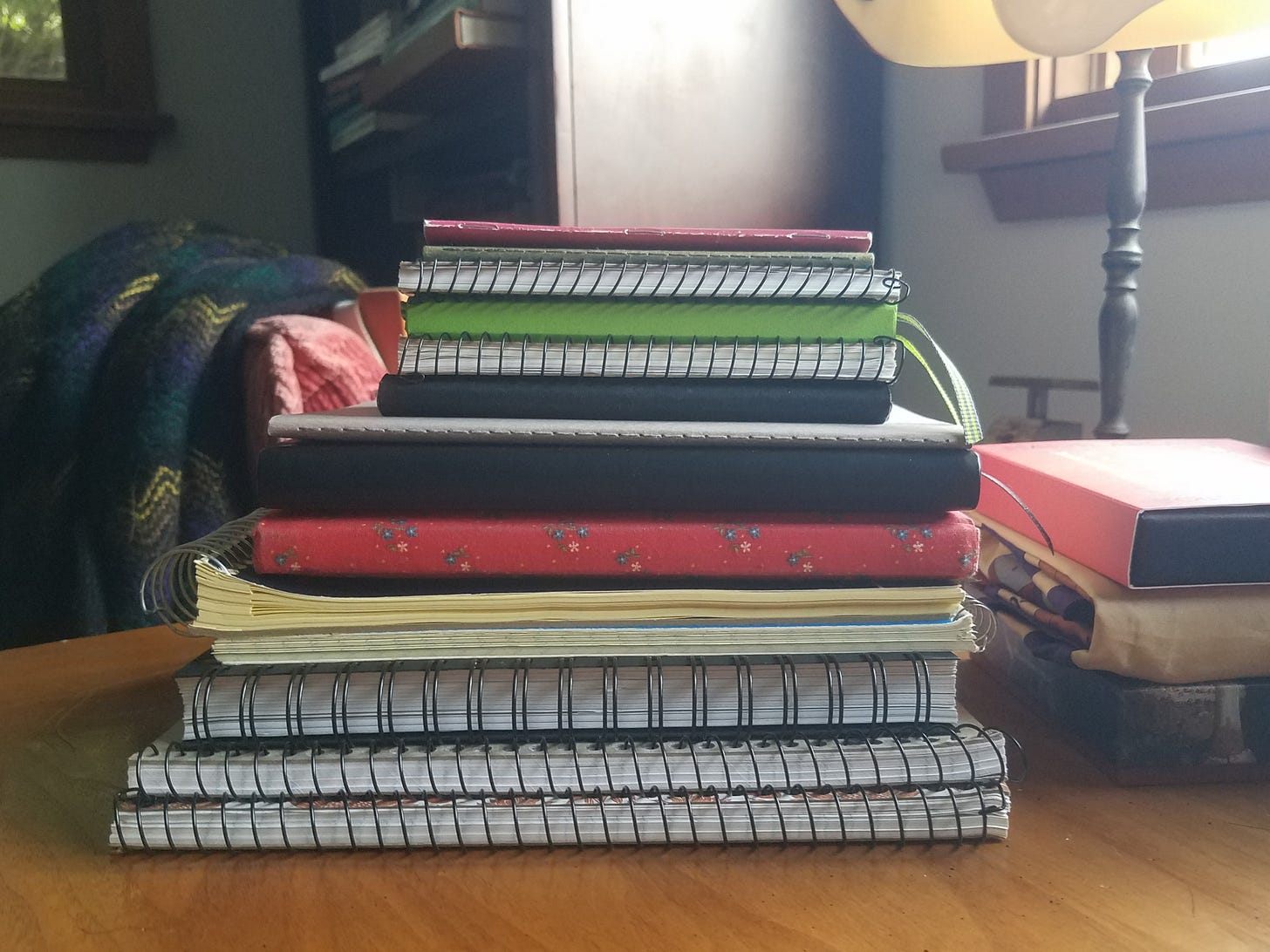

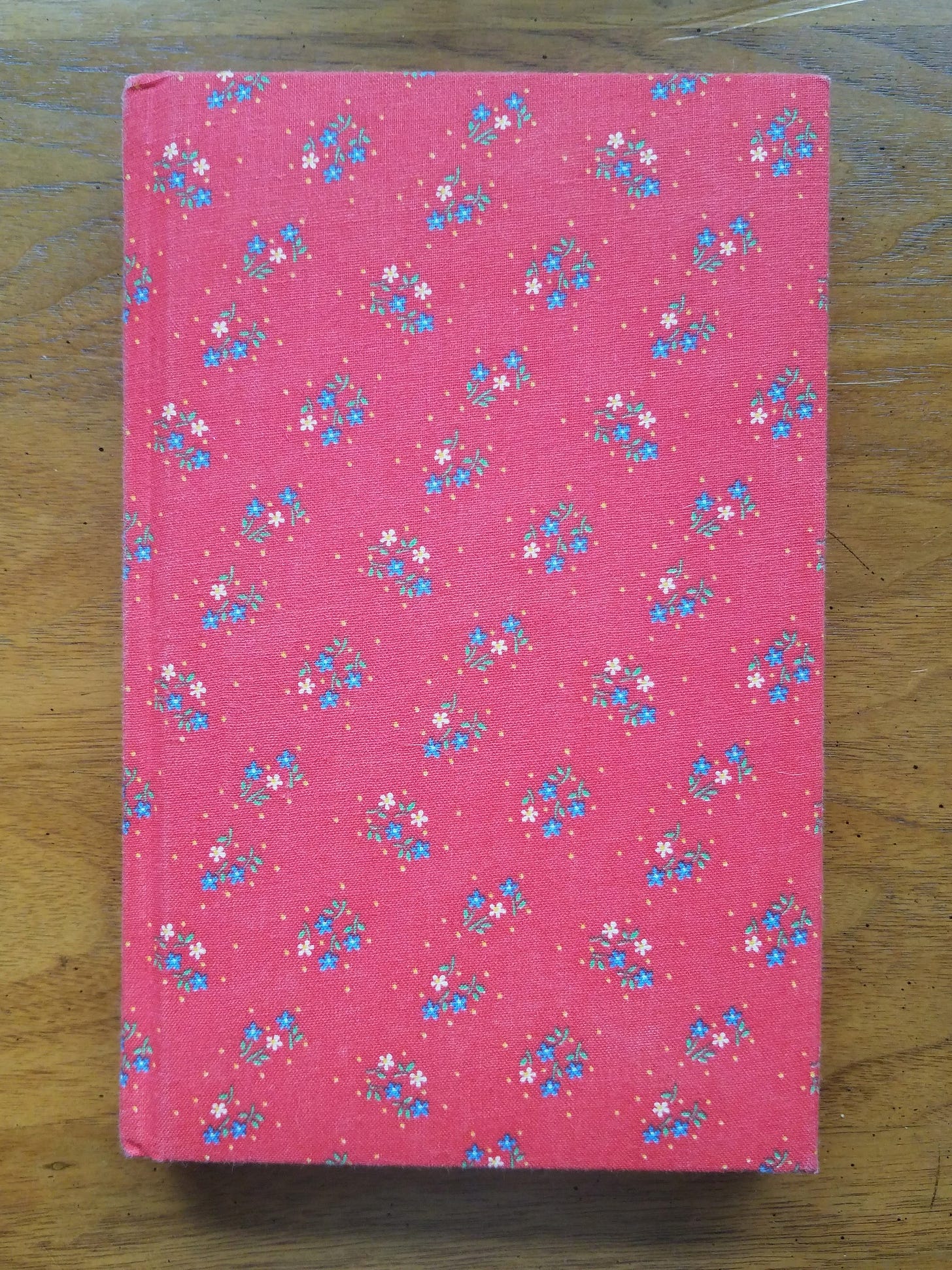

I currently keep a dozen or so working notebooks. Spiral bound notebooks for writing morning pages and early drafts, or for keeping a modern commonplace book. Pocket notebooks for stray thoughts, overheard conversation and interesting facts; for recording progress in different hobbies; for tracking and managing personal finances. Composition notebooks for reading and film logs. A saddle stitch Moleskine journal for undated, sporadic diaristic entries. A lunar planner with prompts for writing, reflection, and ritual practices. A black Rhodia faux-leather bound notebook, a gift from a friend, for notes on the tarot and card readings. A red clothbound journal printed with ditsy white and blue flowers, purchased impulsively from an elderly neighbor’s yard sale a few years ago, where I now keep a sort of epistolary diary of letters to my mother, who died last January and left me, I’ve found since then, with only more to say to her.

If I include my digital note-taking the count swells more. Recently I began keeping a “process journal” in a text file on my laptop, after reading about author Ruth Ozeki’s practice of doing so for the past three decades. The word-search-ability and ongoingness of a continuous text file immediately appealed to me, a dream in contrast with my often chaotic disarray of half-filled paper notebooks, the contrary appeal of which I would also be lying if I denied. Is it because I’m a Libra? Perpetually wavering between opposites, never making up my mind.

Libra is the only zodiac sign represented by an inanimate object, the scales; the other eleven signs of the zodiac are represented by animals or mythical creatures.

I’ve been an amateur notetaker for most of my life, perhaps a natural situation for a lifelong reader and writer. My note-taking practice began with diaries I could only seem to write in sporadically, by instinct or absentmindedness resisting conventional daily recordings, and preferring instead the spontaneous, idiosyncratic, fragmentary entry. In my teens I dropped dated diaries, replacing them with blank journals that served as hybrid writer’s notebooks and scrapbooks. These were as much an opportunity for writing as for improvisational flair in the form of pressed flowers, doodles, and movie ticket stubs tucked in at random with poem drafts and journaling, quotes copied from books or dialogue eavesdropped at the coffee shop downtown.

“To take notes is to play the scales of literature,” said Jules Renard. Who also said he mainly took notes from memory. And then, “my imagination is my memory.”

And then I stopped keeping notebooks for a while, though I continued penciling marginalia in books, even when reading “for pleasure”, which I took to mean reading with no expectation of a written response for academic or publishing purposes. “Do you ever read anything for fun?” asked my then boyfriend, on a trip to our local Borders where he watched me buy a copy of Moby-Dick with pointy-headed satisfaction. I was at a loss to parse a distinction between unassigned and leisure reading.

“Had he not warned me,” Joan Didion writes of her late husband, “when I forgot my own notebook that the ability to make a note when something came to mind was the difference between being able to write and not being able to write?”

Years later we split up and I moved out of our one bedroom apartment in Pacific Grove, and threw all my journals and diaries from adolescence through young adulthood into the dumpster in the carport of our building. This was a double betrayal in the sense that I had previously promised these journals to a friend, who’d expressed interest in having them when I teased that I might someday throw them in the ocean. Which would have been poetic, if no less foolish.

“You would do better,” says Molloy in the first book of Beckett’s darkly comic existentialist trilogy, “at least no worse, to obliterate texts than to blacken margins.”

I threw out my childhood journals in part because I expected to fill future notebooks with more important, literary stuff in college. After high school I’d taken a gap year to travel and determine what I wanted to study, if I wanted to attend college at all. That gap year sprawled into four indulgent years of recreational activities and day drinking funded by restaurant tips, and enabled by my skeptic boyfriend, and no travel. Tiring of my budding alcoholism and circumscribed territory, I’d enrolled at the local community college with a plan to transfer to a university and complete a B.A. in English, to no clear financial end. I had read Harold Bloom—also purchased on a lark at Borders—and so believed, with inexplicable certitude, in the dollar-less value of a liberal arts education. Equipped with purpose, I tossed out my juvenilia with an austerity it now startles me to recall, and moved to Los Angeles to begin my serious, scholarly life at UCLA.

In ancient Rome, the libra was a unit of weight more or less equivalent to the pound. Roman coin denominations were based on the libral standard; the British pound is a translation of the Roman libra.

What is the point of all this? Where and to what are my notes pointing? Are they improvisational, like notes in jazz scales? Or meditative, noting as an instance of noticing. Are they a practice in themselves, what might be called “notework”? Or merely ancillary to the real, capitalized work of Writing. (The Latin root word ancilla means a female servant. Am I so preoccupied with the “subordinate” activity of note-taking because I’m more comfortable here, in the realm of the secretarial, than I am in the realm of the Authorial?) Can I rightfully call myself a Writer, when what writing I do produce is so slight, disjointed, aimless? Can we make meaning from notes alone, without a narrative structure to incorporate them into a coherent whole, one proverbially greater than the sum of its parts? Why does a person accrete so much notework before finishing a single book project of their own?

During construction of the Bloomberg London headquarters building in 2014, Roman promissory notes from the first century AD were discovered among hundreds of well preserved artifacts buried beneath Queen Victoria Street in the city’s financial center. The notes were etched in cursive Latin on wooden tablets covered with beeswax.

More, am I really attempting to retrieve my discarded childhood notebooks from underneath some trash heap, by now long buried in a landfill somewhere, just south of the Moss Landing Power Plant? (Or salvage their parts, the way my dad would collect scrap metal and divide it by type into drum barrels in our driveway, to haul to a scrap yard where they’d be weighed and sold at market rates.) Do I, at bottom, wish to rectify an old betrayal? Is it that I’m now the same age my mother was when I was born, exactly half her age when she died, and I am now preoccupied with a suddenly urgent calculus of meaning and time? (Or is it an algebra problem, an equation I’m working to balance out.) Who am I hoping to find here, what recover?

“If you can’t keep up take notes,” my mother once joked, in a text message.