on weaving

dreams and play

Dreams are theatres which put on the appearance of a play in order to slip other unavowable plays between the lines of the avowal scenes: you reader-spectator are aware of this but you forget what you know so you can be charmed and taken in. You connive with your own trickery. You pull the wool over your eyes.

—Hélène Cixous, Dream I Tell You

Though they are essentially traces of the past, notes are, at the same time, uniformly forward facing. We assemble them always with some notion, however dim, of future use. Notes lend themselves to assemblage, the way magazine clippings do to collage, or fabric pieces to quilts. Discrete units, they pull toward natural counterparts, like atoms drawn together, bonding through proper valence. Soon, and seemingly from empty air, molecules appear and constellate into compound molecules, amino acids and nucleotides, spindly double helixes. Patterns start to emerge and reveal the weave of things. We pick up one thread and find it’s knit together with several others. With time and taking a few steps back we might glimpse the whole fabric. This can seem almost like a magic trick. It will startle us to remember that we’ve been weaving the thing all along, the animal suspended in its own web of significance.1 As with any paradox there is a dreamlike quality to all this. Alice before the mirror, viewing in her left hand the orange she feels in the grip of her right. Or watching from the circus audience an aerial act in which you find, to your surprise, you are an unwitting performer. This can be thrilling, and it can feel slightly paranoiac—if not the full blown craze of conspiracy theory, then a milder version.

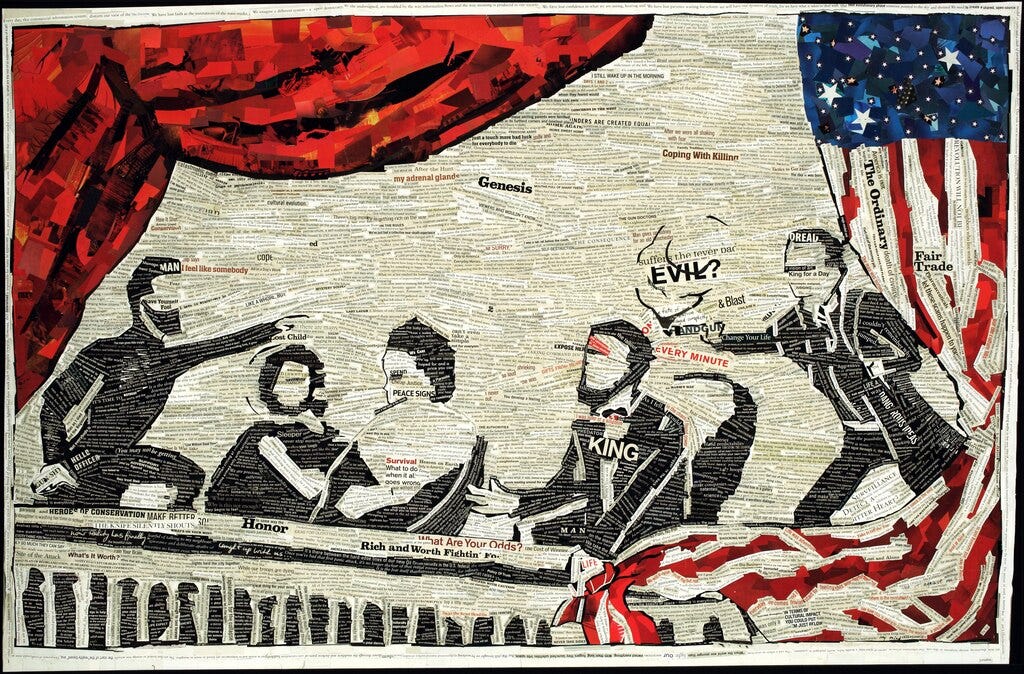

Collage is a demonstration of the many becoming the one, with the one never fully resolved because of the many that continue to impinge upon it.

—David Shields, Reality Hunger

The opening scene of Throne of Blood, Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 adaptation of Macbeth set in feudal Japan, distills Shakespeare’s weird sisters into one forest spirit crouched at a spinning wheel, reeling a gossamer thread when two samurai generals (one is the film’s Macbeth, played by Toshiro Mifune) discover her latticed bamboo hut.2 She incants the tragic general’s prophecy while turning her wooden wheel inside her den. The spirit embodies the Moirai of Greek mythology, as well as Arachne, the masterful weaver transformed into a spider for her boasting.3 For contemporary Japanese audiences this scene also recalls the Noh play Kurozuka, or Black Mound, in which two monks seek lodging in a poor woman’s hut, where they discover a room containing a pile of skeletons. The play’s story comes from the tradition of the onibaba, or “demon hag,” a monstrous figure who appears regularly in minkan denshō folklore. With one shot Kurosawa entwines legend, myth and dramatic convention in a deft cultural translation of Elizabethan theater.

Use the word in a sentence. In grade school we were frequently assigned vocabulary exercises with instructions to write sentences using each new word. A proficient reader and writer, I was bored by the easy task of generating ten unrelated sentences. I began composing narrative paragraphs that by the end had incorporated each vocabulary term. The exercise became a word game that I played, a lexical cat’s cradle. For years I forgot about this practice, and having kept none of these school assignments I was only reminded of it when my mother would tell the story, one episode of many in the saga of my growing personhood. A loose thread that she carefully wove back into our cloth of family myth. Much of childhood can be like this: a forgotten dream reflected back to us through someone else’s stories.

The problem is, if I didn’t find this sentence my thoughts would be cut off, and thoughts which have been cut off are like a cut-off kite, you’ll never be able to retrieve it again. Without a sentence you just can’t think, because thinking is like a chain, each ring is linked to the next one.

—Gao Xingjian, The Other Shore

Among some playbills in a shoebox in our closet there is a small sheet torn from an unlined bound journal (the only surviving fragment of my teenage journals) with an affixed half-page flyer for our high school production of The Other Shore, an experimental play by then recent Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian. My part in the play was minor. During a climactic scene I would step out from the wings with cello and bow and, seating myself on the edge of a black rehearsal block downstage, play the elegiac main theme from Schindler’s List while actors upstage executed an increasingly violent pantomime. Because I faced the audience I could only overhear the action in bursts of muffled footsteps or soft thuds of bodies on the minimalist set. The play’s Chinese title, Bi’an—literally “the other (or opposite) shore”—refers to the Buddhist concept of perfection or transcendence, paramita. (Gao troubles this concept in the opening stage directions by setting the location of the action “from the real world to the nonexistent other shore.”) The play begins with a group of actors playing a game with ropes, “a manifestation of all kinds of interpersonal relationships,” the scene’s speaker glosses. Ropes become steadily more entangled, creating knotty arrangements of the actors holding onto them. “Society,” the speaker narrates, “is complex and ever-changing, we’re constantly pulling and being pulled. (Pauses.) Just like a fly that’s fallen into a spider’s web. (Pauses.) Or just like a spider.”

Chinese legend attributes the discovery of sericulture and the invention of the silk reel and loom to the empress Leizu, who is known as the “Silkworm Mother.” She is said to have dropped a silkworm cocoon into a cup of hot tea and watched as the precious thread unspooled to reveal its source.

André Breton, in an introductory note on Lewis Carroll for his own Anthology of Black Humor, sees in play (as manifested in “nonsense” literature) an adaptive mechanism for adult life. “The mind,” he assures us, “placed before any kind of difficulty, can find an ideal outlet in the absurd. Accommodation to the absurd readmits adults to the mysterious realm inhabited by children. Children’s games (beginning with simple ‘word games’), as a lost means of reconciling action and reverie so as to achieve organic satisfaction, thus remains their dignity and validity.” Rather than the self-serious adult, Breton finds dignity in the figure of the playful child, on which he then pins the outsized role of emancipator:

In the shameful chains of those days of massacre in Ireland, of nameless oppression in factories where the ironic accounting of pleasure and pain preached by Bentham was established, while from Manchester rose in defiance the theory of free trade, what had become of human freedom?4 It rested entirely between the frail hands of Alice, in which this curious man had placed it.

Carroll was himself uneasy around adults. He preferred the company of children, in particular young girls, the paragon of which he esteemed a seven-year-old “child-friend” named Alice Liddell, who would become his primary model and muse.

In English the matrilineal side of the family is called the “distaff side,” the distaff having been emblematic of women’s work and female authority since at least the medieval period.

The loom and distaff are common loci of female power in classical mythology: Penelope tricks her unwelcome suitors into an indefinite state of delay with the pretense of weaving a burial shroud that she secretly unravels each night; (Does her handiwork mirror the thousand stories Scheherazade narrates to preserve herself from her femicidal husband?) Calypso detains Odysseus on her isle by singing an enchanting song at her loom, where she passes her golden shuttle back and forth, drawing weft through warp; Ovid gives a brutal account of the rape of Philomela who, after her tongue is cut out by her rapist, weaves a tapestry depicting the assault, initiating both a revenge plot against her assailant and her own transformation into a nightingale. Vindication, it turns out, is bound by its own constraints.

A text is something woven. Like textile it descends from the Latin verb texere, meaning “to weave or plait.”

Originally a professional title, “spinster” became a legal term for an unmarried woman sometime around the turn of the 17th century. Like widows and unlike married women, spinsters could own property and retain some financial autonomy.

A denouement is an unraveling, the untying of a knot. (When a play ends with a wedding, convention tells us, we know it is a comedy.)

In her influential essay on narrative structure, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Ursula K. Le Guin borrows from an evolutionary theory outlined by Elizabeth Fisher that contends the first cultural device, rather than a weapon for hunting, was a container for gathering food, most likely a kind of woven sling or net.5 Le Guin argues against predominant heroic narratives and their spearlike linear structures, and suggests the sack or bag as a more fitting shape for fiction. “A book holds words,” she writes. “Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.”

Casting a spell, telling a yarn. The craft of women.

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

Clifford Geertz works up this metaphor in his 1973 anthropological text The Interpretation of Cultures, were he also develops the concept of “thick description”, demonstrated in the seminal essay “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight.” Geertz attributes the term “deep play” to the 18th century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who defines it as a type of game in which the stakes are so high no rational person would engage in it.

“Wyrd” in Old English meant fate or destiny, and was a reconstruction of an earlier Germanic reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European root “wert,” which meant “to turn or wind.” The modern adjectival sense of “uncanny, supernatural, or skilled in witchcraft” began with the Middle English epithet “weird sisters,” originally used to describe the three fates in mythology.

The three sisters who spin, measure, and cut the thread of each person’s life were known as Fates, or Moirai, from the Ancient Greek for “lots” or “portions.”

The Japanese title for Throne of Blood is Kumonosu-jō, or The Spider Web Castle. Instead of Birnam Wood, the castle in the film is located in Spider Web Forest, where the spirit spins her thread.

The jorōgumo, or “woman-spider” is another popular supernatural creature in Japanese folklore.

Breton here mocks the basic tenet of utilitarian philosophy: “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.” This “greatest happiness principle” inspired Jeremy Bentham’s most well-known innovation, the Panopticon prison design.

Fisher’s Woman’s Creation: Sexual Evolution and the Shaping of Society was nominated for a Pulitzer in 1979. The author would commit suicide in her studio on New Year’s Day in 1982, four years before the publication of Le Guin’s essay. None of the 1979 Pulitzer Prize winners were women.