on limbos

guides and dancing

You see we all thought the ride would be lovely and worth the trip, which it was, but now we cannot go anywhere having already been everywhere. No, do you understand how realistic it all is?—John Ashbery, Girls on the Run

You know then that Dante accepts the existence of angels who were neutral in the quarrel between God and Satan. And he puts them in limbo, a sort of ante-chamber of his hell. We are in the ante-chamber, my friend.

—Albert Camus, The Fall, trans. Justin O’Brien

There is of course a quality of in-betweenness to note taking. I read a text or overhear a stranger’s conversation, and in going to note down some detail I’m no longer a passive observer; yet neither am I a full participant in the action. I am somewhere between the two, neither audience nor actor. (In our high school theater productions, after dress rehearsals and performances the cast would gather for notes, with the actors seated in the audience and the director reading notes from the stage.) My concern as note taker, unlike the author, is not the reception or interpretation of my work, which remains, for the moment, private; nor is it the articulation of inner experience, as with original writing or casual talk with a friend. It’s the other way around: I am concerned with incorporating an outer experience into my inner world. Struck by something in the text or my surroundings, I write it down with all the other noteworthy items. I do this not just to remember, but also to reuse, to repurpose after some indeterminate period of reflection, when the essence of the notes can be extracted, absorbed, composted, and finally reconstituted as a new organic thing. The notebook is like the chrysalis where the caterpillar liquidates and transforms into emergent imago. In other words, a kind of limbo, where ideas linger, awaiting their mysterious rebirth.

To each his suff'rings: all are men, Condemn'd alike to groan, The tender for another's pain; Th' unfeeling for his own. Yet ah! why should they know their fate? Since sorrow never comes too late, And happiness too swiftly flies. Thought would destroy their paradise.—Thomas Gray, “Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College”

Violet Paget was a Victorian feminist author of supernatural fiction, essays on aesthetics and travel, historical studies and art criticism, and pacifist philosophy published under the pseudonym Vernon Lee.1 She came to be regarded, along with her intellectual guide and originator of aestheticism Walter Pater, as an authority on the Italian Renaissance. Paget’s cosmopolitan essays and ghost stories were admired by contemporaries like George Bernard Shaw and, grudgingly, her dubious friend Henry James.2 Paget developed several longterm intimate companionships with female friends and collaborators, the most fruitful with the artist Clementina “Kit” Caroline Anstruther-Thomson, with whom she co-authored Beauty and Ugliness and Other Studies in Psychological Aesthetics in 1912. From 1901 to 1904 Paget recorded her physiological responses to artworks in her “Gallery Diaries”—published as the centerpiece of Beauty and Ugliness—having been inspired to begin this practice after observing Kit’s sensuous approach to art viewing.3

The rule that makes its subject weary is a sentence of hard labor. —Heraclitus, Fragments, trans. Brooks Haxton

Paget’s 1897 Limbo and Other Essays is dedicated to her close friend Mabel Price, “in memory of many rambles and hopes of many more amongst hills, books, and unrealities.” The title essay begins with an epigraph from Canto IV of Dante’s Inferno. The lines express Dante’s grief for the “many worthy souls” suspended in Limbo, and occur in the poem as an empathic response to his guide Virgil’s characterization of himself and other unbaptized souls there: “Through this, no other fault, / We are lost, afflicted only this one way: / That having no hope, we live in longing.”4 The brief essay is a dense rhetorical examination of concepts of genius, artistic reception, timing, historical materialism—“it is as well we realize that, although genius be immortal, poor men of genius are not,” the author points out—shyness, and happiness, among others. “Limbo” ends on a witty, almost wistful note of carpe diem. “As we grow less attached to theories,” Paget reasons, “and more to our neighbors, we recognize every day that loss, refusal of the desired, has not by any means always braced or chastened the lives we look into; we admit that the Powers That Be showed considerable judgment in disregarding the teachings of asceticism, and inspiring mankind with an innate repugnance to having a bad time.”

Imagine the gods: tall, blond surfers, lounging on beaches and in gardens flooded by brilliant sunshine, listening to any kind of music they choose, intoxicated by every kind of stimulant, high on meditation, yoga, bodywork, and ways of improving themselves, but never taxing their brains, never confronting any complex or painful situation, never conscious of their true nature, and so anesthetized that they are never aware of what their condition really is.

—Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

Allor si mosse, e io li tenni dietro.5 “Have you picked up a copy of The Stranger yet?” We’re on Beacon Hill twenty years ago, looking across the freeway to downtown Seattle when my guide asks me this. I’d made the 15 hour drive up from Monterey that day, and after getting settled at my friends’ split level house share, he’s invited me on a walk down the hill to an outlook with a view of the city, a cluster of tall buildings in the middle distance. Lit office windows blink against a dark skyline flanked by the Puget Sound on the west and Lake Washington on the east. A steady fizz of tires on wet asphalt rises from the busy I-5 below us. His question catches me off guard. “You mean, by Camus?” I ask, surprised. He grins, eyes glinting back at the line of brake lights leading into the city. He explains that The Stranger is Seattle’s weekly paper, and we share a laugh, then walk back up the hill to the house, where his roommates will open a case of Rainier and I’ll drink my first underage beer.

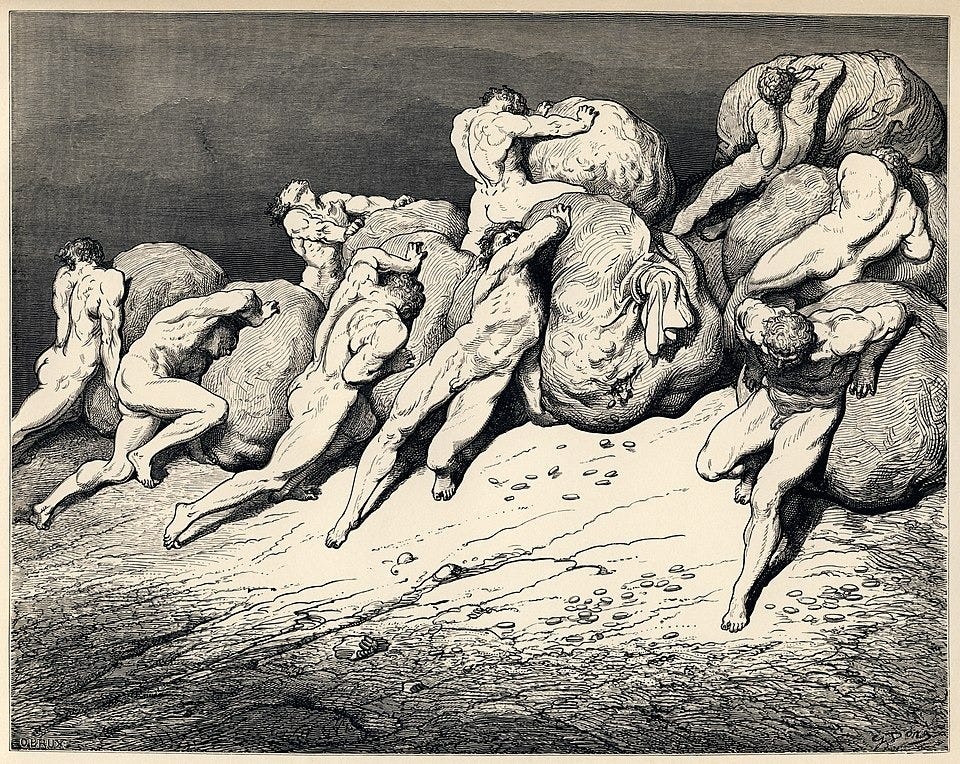

As winter starlings riding on their wings Form crowded flocks, so spirits dip and veer Foundering in the wind’s rough buffetings—Canto V, The Inferno of Dante, trans. Robert Pinsky

The next morning we’ll stop for coffee on Capitol Hill and I’ll take as a souvenir a small white pin-back button with “Perkatory Cafe” underscored by a row of orange flames. He’ll leave for work and I’ll drive to the University of Washington campus where I’ll give a clumsy cello audition to a stoic panel of music program judges.6

Afterwards he’ll take me on a tour of local haunts, and we’ll ride the night ferry to Bainbridge Island and back, drinking from brown paper bags and smoking cigarettes on deck, watching the gleaming buildings draw nearer through soft rain. A Category 1 windstorm will arrive in the sound on my last day in the city, when he’ll bring me to Columbia Tower, the tallest skyscraper downtown. The upper floors and observatory will be closed due to hazardous wind speeds—the tops of the tallest buildings sway in winds this high, he’ll tell me—so we’ll take the operating elevator to a conference room on the 40th floor for a view; this will still be the highest floor I’ve ever been on, and on the way up we’ll joke about the never ending elevator ride. We’ll walk back through empty streets, winds soughing between the glass facades of buildings and buffeting us along the pavement. We’ll link arms and duck into the hurricane blows, the only ones out in such wild weather, gusts carrying our breath and laughter away.

The limbo dance originated in the Caribbean during the 19th century. It was traditionally performed at wakes in Tobago and Trinidad as a ritual symbolizing the cycle of life and death. Guyanese writer Wilson Harris suggests that the dance also symbolized the threshold crossed by enslaved peoples when boarding slave galleys, where it was performed by captives on deck during forced exercise regimens.7

What do I care for a hell for oppressors? What good can hell do, since those children have already been tortured? And what becomes of harmony, if there is hell? I want to forgive. I want to embrace. I don’t want more suffering. And if the sufferings of children go to swell the sum of sufferings which was necessary to pay for truth, then I protest that the truth is not worth such a price.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Constance Garnett

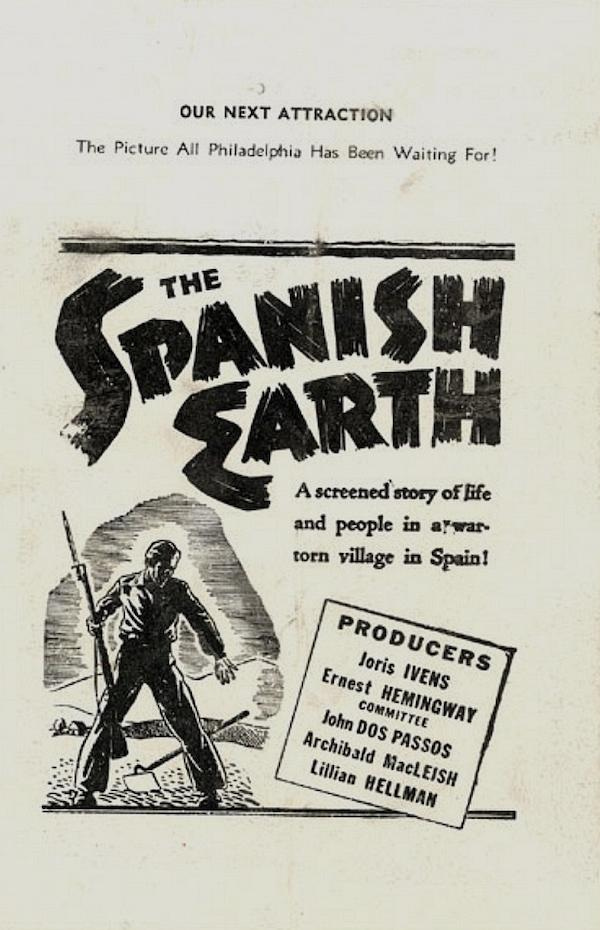

Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not is a Depression era novel about a fishing boat captain who resorts to black market smuggling after a wealthy customer skips out on his lengthy tab. The broke captain ferries alcohol, immigrants, and revolutionaries between Havana and Key West to make a living. Chapters alternate between scenes of desperate poverty and crime and contrasting depictions of the decadent lifestyles of affluent yacht owners. Hemingway wrote the novel while living in Key West, where he purchased a boat in 1934 and spent much of his free time sailing the Caribbean. He left for Spain in 1937 to report on the Spanish Civil War and produce The Spanish Earth, an anti-fascist film co-written by Hemingway and John Dos Passos. A version of the film narrated by Orson Welles screened at the White House in advance of its premiere that July.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the six bardos are states of consciousness and transition experienced at each stage of life and death. Three bardos are experienced during life: the Bardo of Birth, the Bardo of Dreaming, and the Bardo of Meditation; three are experienced in death: the Bardo of Death, the Bardo of Reality, and the Bardo of Rebirth. The term bardo in Tibetan means “between two.” It refers generally to the state of transition between two lives, and is sometimes compared to theological concepts of Limbo.

Howard Hawks’s 1944 film adaptation of To Have and Have Not moves the setting to a Vichy controlled Martinique. Hawks omits the book’s themes of class and economic inequality and instead focuses heavily on the love affair between the boat captain, played by Humphrey Bogart, and an attractive drifter with a husky voice, played by Lauren Bacall. Captain and drifter are drawn together by circumstance—neither can afford to leave the island—and mutual attraction. (Bogart and Bacall would begin an off-screen affair during production and marry the following year.8) Whereas economic forces press the captain of Hemingway’s novel into a life of crime, the film version’s moral dilemma revolves around whether he can remain neutral under increasing pressure from the oppressive Vichy regime.

But this little difference, according as the sentence runs “Satan is the Adversary” or “The Adversary is Satan,” repays our further scrutiny. For the inversion, the putting of an Adversary, i.e. a human being or group of human beings, in the place of Evil as such, happens to be one of Satan's oldest and most successful wiles, which he compasses (as I have ventured to make him explain) by means of two most serviceable minions of his, namely Delusion and Confusion. Let us look further still into the matter. Take the formula “Satan is the Adversary”; there Satan—meaning the infliction of useless loss and pain, the fruitless sacrifice (as distinguished from the enriching exchange of good) Satan, as all religions have taught, is, actually and potentially, in all and every one of us alike. Hence our chief dealings and wrestlings with that Old Enemy must be in ourselves.

—Vernon Lee, Satan the Waster

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

nota bene

Iris Jamahl Dunkle shares a recent encounter with Vernon Lee at the Met that you can read about here. If you’re not already subscribed to her excellent weekly newsletter dedicated to surfacing the work of marginalized women, Finding Lost Voices, you really should sign up now.

Paget’s paternal grandfather was an émigré French nobleman named De Fragnier who took his wife’s name when they married. Her maternal grandfather was a Welsh landowner who made his fortune in Jamaica. Lee’s pseudonym comes from her half-brother, the poet Eugene Lee-Hamilton, who composed sonnets by dictation after suffering a sudden collapse that left him paralyzed.

Paget’s first novel was dedicated to James, who was severely critical of her fiction debut in their correspondence following its publication. The friendship ended after Paget published “Lady Tal,” in which a character based on James is portrayed as timid, self absorbed and hostile toward women writers.

See “Unrecovering Vernon Lee” in Simon Reader’s Notework: Victorian Literature and Nonlinear Style.

Trans. Robert Pinsky.

“Then he set out, and I followed where he led.” Canto I, The Inferno of Dante, trans. Robert Pinsky.

My audition piece was the cello solo from the first movement of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major. (Audio clip from the Al Goldstein collection, “Selections from the concert of December 2006.” Creative Commons.)

The only known extant manuscript of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos was nearly destroyed in World War II, during its transportation via train from the Royal Library of Berlin to Prussia for safekeeping; when the train came under aerial bombing a librarian escaped into nearby woods with the scores tucked under his coat. See Eric Siblin’s The Cello Suites: In Search of a Baroque Masterpiece.

A recording of Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 was included on the Voyager Golden Record, a time capsule launched into space in 1977 on the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 space probes, both of which have since reached interstellar space and are currently the furthest anthropogenic objects from Earth.

“The beginning of African American culture is not to be sought in the image of tight-packing...but rather in the few moments and marginally expanded space on the deck (under the watchful eye of the crew), where the African captives replicated their physical contortions in dance. In this way, Harris seeks to formulate ‘a philosophy of history which is original to [the Caribbean] and yet capable of universal application.’ This philosophy is thus defined by what Homi Bhabha calls the space in-between, rejecting the stringent opposition between above and below, between civilized and savage, that informs the discourses of slavery’s defenders and its opponents.” See Black Imagination and the Middle Passage, ed. Maria Diedrich, Henry Louis Gates Jr., & Carl Pedersen, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Bacall was 19 during filming; Bogart was 45 and married to his third wife. Hawks reportedly disapproved of the affair, which the actors continued in secret. The director cast Bacall at his wife Nancy’s suggestion after she noticed the 18 year old model on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar. The leads’ nicknames for each other in the film, “Slim” and “Steve,” were the pet names used between the director and his wife.