on copies

samizdat and palimpsests

The first office of justice is to keep one man from doing harm to another, unless provoked by wrong; and the next is to lead men to use common possessions for the common interests, private property for their own.

—Cicero, On Duties (trans. Walter Miller)

To do what is forbidden always has its charms, because we have an indistinct apprehension of something arbitrary and tyrannical in the prohibition.

—William Godwin, Caleb Williams

Every man should be capable of all ideas, and I believe in the future he shall be.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” (trans. Andrew Hurley)

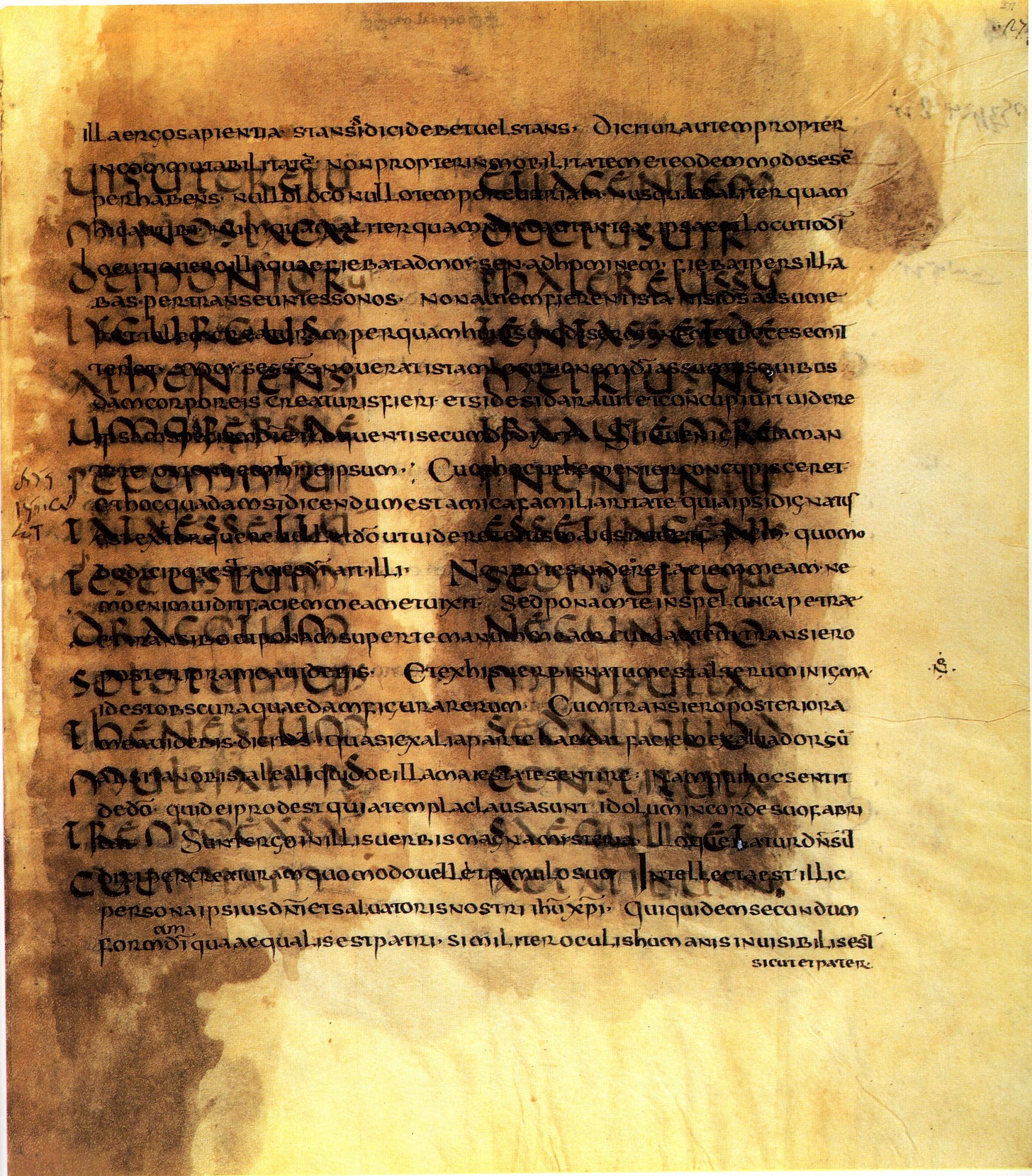

Much of note taking is—that frequently maligned rote—copying. Plunging into the sacred fount of original sources, the notetaker resurfaces with some salvage that, always already claimed by enterprising parties, she resigns herself to duplicating in her notebook for future reference. How much simpler to own an archive of treasured primary texts, cataloged and arranged for optimum utility, to consult as needed. Yet the obstinate notetaker can’t content herself with even the finest libraries. She requires no less than her own concordance to her personal repertoire of literary and artistic works. After even a few short years of such labor the page count alone will daunt all but the most mulish scribblers, to say nothing of the tedious stewardship involved in managing and organizing and shuffling ever growing piles of paperwork. But in this secretarial work there are certain hidden benefits: her painstaking reproductions, line for line, leave their impressions on her memory too, transferred from page to psyche as if by wispy carbon paper. Like the ancient palimpsest or ashen chalkboard, the copyist’s past traces show through, lend depth and history to each refreshed surface. The notetaker fancies herself like the double of Pierre Menard, who alone could restore that author’s first essays at the verbatim composition of Don Quixote—an accomplishment of obvious and immediate value to her.1 Applied to works in the public domain, it’s easy to appreciate the daring of Menard’s feat; but what happens when we begin tilting at copyright windmills? Can the notetaker still claim the title of noble savant, or does she fall to the demoted rank of errant hack?

While of other law-copyists I might write the complete life, of Bartleby nothing of that sort can be done. I believe that no materials exist for a full and satisfactory biography of this man. It is an irreparable loss to literature. Bartleby was one of those beings of whom nothing is ascertainable, except from the original sources, and in his case those are very small.

—Herman Melville, “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street”

While completing the final installments of his serially published novel Anna Karenina in the late 1870s, Count Leo Tolstoy suffered a nervous breakdown followed by a radical spiritual awakening that would alter the course of his personal and writing life and result in one of the most notorious, devastating, messy marital rifts in literary history. Rejecting all organized religion as well as his own Orthodox upbringing, the aristocratic Russian author began publishing Christian anarchist theosophical tracts in the early 1880s—having been deeply affected a decade earlier by Schopenhauer’s argument for moral asceticism in The World as Will and Representation—writing A Confession, What I Believe, and The Kingdom of God is Within You over the next 15 years, and inspiring the creation of utopian communes around the world like Tolstoy Farm, an ashram in South Africa founded by Gandhi in 1910. Tolstoyans advocated principles of nonviolence rooted in the teachings of Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount; adopted a vegetarian diet and celibate lifestyle; and criticized an exploitative social order created through private land ownership and the state. Troubled by the apparent hypocrisy of a nobleman expounding revolutionary moral philosophy, the Count determined to renounce his vast estate and release all copyrights of his works, to the horror of his wife Sophia.

A long tradition in Christianity also takes the fruits of human creativity to have nonhuman origins and thus assumes that they cannot be bought or sold (nor can they really be forged, plagiarized, or stolen). Such was the traditional understanding for medieval Christians:

Scientia Donum Dei Est, Unde Vendi Non Potest.“Knowledge is a gift of God, therefore it cannot be sold.” To sell knowledge was to traffic in the sacred and thus to engage in the sin of simony.

—Lewis Hyde, Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership

Sophia Tolstaya was a loyal partner throughout the Tolstoys’ long, tumultuous marriage. She gave birth to 13 children, raised the eight who survived childhood while also working as copyist and editor for her husband—she transcribed seven completed manuscripts of his monumental War and Peace by hand, writing by candlelight while the children and servants slept, often deciphering Tolstoy’s minute notes with a magnifying glass—and managed the large family estate at Yasnaya Polyana.2 After his spiritual rebirth, however, the couple’s suddenly divergent views on private property and inheritance sent deep, irreparable fissures through the partnership. “The Tolstoys began to fight constantly,” writes author Elif Batuman, “long into the night. Their shouting and sobbing would make the walls shake. Tolstoy would bellow that he was fleeing to America; Sonya would run screaming into the garden, threatening suicide.”3 During this period Tolstoy wrote The Kreutzer Sonata, a philosophical novella about the brutal murder of a wife by her husband that argues for sexual abstinence. “Anyone investigating foul play in the death of Tolstoy would find much to mull over in The Kreutzer Sonata,” speculates Batuman.

This, then, is the most comprehensive bond that unites together men as men and all to all; and under it the common right to all things that Nature has produced for the common use of man is to be maintained, with the understanding that, while everything assigned as private property by the statutes and by civil law shall be so held as prescribed by those same laws, everything else shall be regarded in the light indicated by the Greek proverb: “Amongst friends all things in common.”

Furthermore, we find the common property of all men in things of the sort defined by Ennius; and, though restricted by him to one instance, the principle may be applied very generally:

"Who kindly sets a wand'rer on his way Does e'en as if he lit another's lamp by his: No less shines his, when he his friend's hath lit."In this example he effectively teaches us all to bestow even upon a stranger what it costs us nothing to give.

—Cicero, On Duties (trans. Walter Miller)

Samizdat is a form of dissident underground publishing that arose in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death, during the period that would become known as “the thaw,” as a strategy for circumventing state censorship. Censored texts were reproduced in secret, hand-typed on privately owned typewriters in duplicate copies using carbon and tissue paper, and distributed through activist networks. Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago was the first novel to be distributed as samizdat, only officially available in the West through an Italian publisher in November 1957. Recognizing the novel’s efficacy as anti-Communist propaganda, in 1958 the CIA printed a bootlegged version, slipping one thousand Russian language copies to Soviet citizens traveling abroad in Brussels, Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich, London, and Paris.4 The term samizdat comes from a pun coined in the 1940s by avant-garde poet Nikolay Glazkov, in a note to the front matter of his hand-typed poetry pamphlets that, roughly translated, read “Myself by Myself Publishers.”

“It is a good thing to do. And it will be good for you to do it; but if you do not do it, that is your affair. It means that you are not yet ready to do it. The fact that my writings have been bought and sold during these last ten years has been the most painful thing in my whole life to me.”5

Three copies were made of this will, and they were kept by my sister Masha, my brother Sergei, and Chertkov.

—Ilya Tolstoy, “My Father’s Will,” Reminiscences of Tolstoy (trans. George Calderon)

Although she eventually persuaded him to retain the copyrights for works published prior to his religious awakening, Sophia worried her husband would rewrite his will and transfer all control to Vladimir Chertkov, Tolstoy’s intimate companion and fellow Christian anarchist. This scenario came to pass in 1909, when Tolstoy signed a secret will on the stump of a tree in the woods of their country estate: “He left all his copyrights in the control of Chertkov and of his youngest daughter, Sasha, a fervent Tolstoyan. This had long been Sonya’s worst fear—‘You want to give all your rights to Chertkov and let your grandchildren starve to death!’—and she addressed it through a rigorous program of espionage and domestic sleuth work. She once spent an entire afternoon lying in a ditch, watching the entrance to the estate with binoculars.” Sophia’s persistent snooping after the hidden will would ultimately lead to Tolstoy’s abrupt departure from their home just ten days before his death, in the stationmaster’s apartment at the Astapavo train station on November 20, 1910.

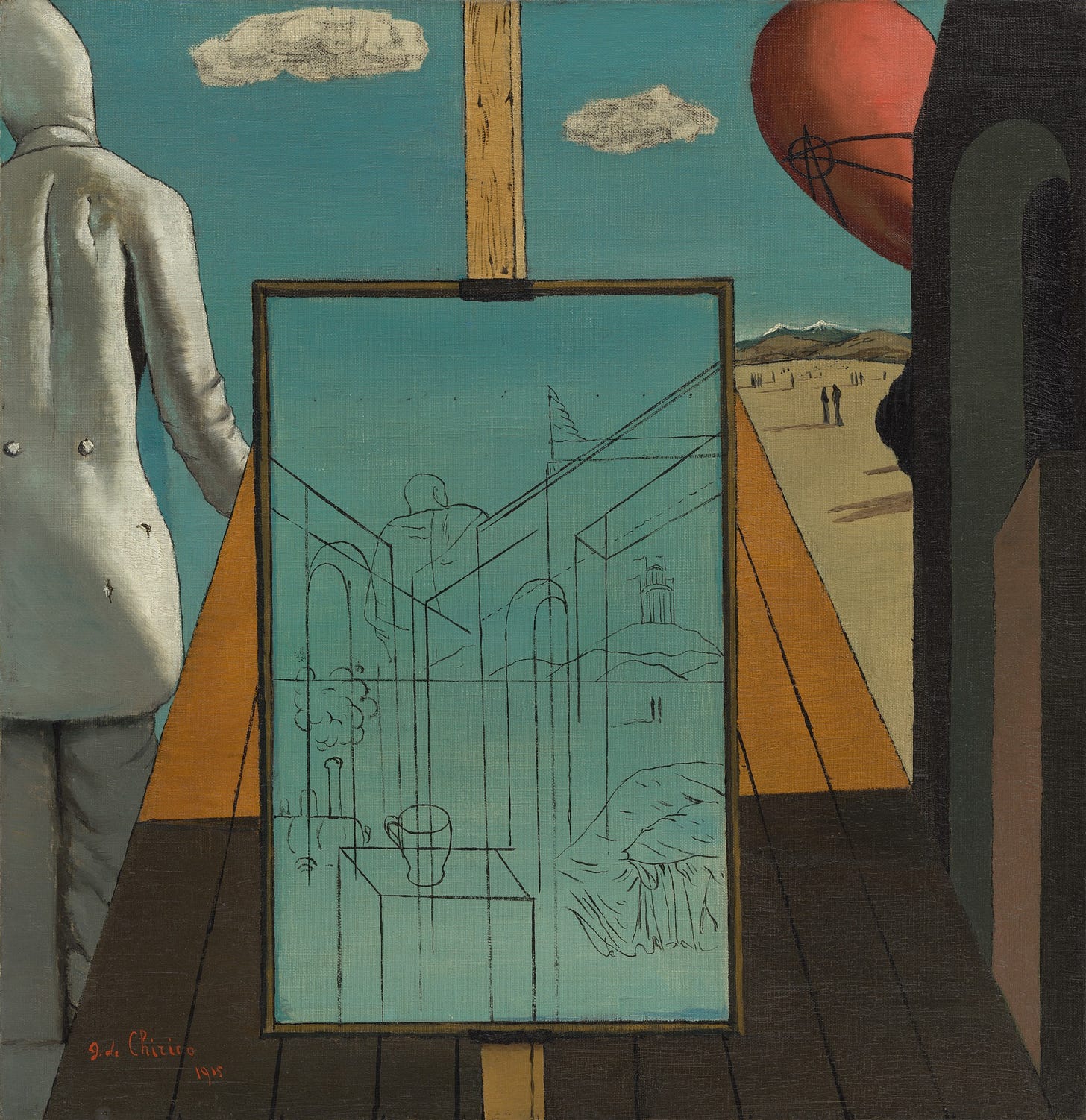

A guy in the cafeteria of this one museum said that nothing gives him such great satisfaction as being in the presence of an original artwork. He also insisted that the more copies there are in the world, the greater the power of the original becomes, a power sometimes approaching the great might of a holy relic. For what is singular is significant, what with the threat of destruction hanging over it as it does. Confirmation of these words came in the form of a nearby cluster of tourists who, with fervent focus, stood worshipping a painting by Leonardo da Vinci. Just occasionally, when one of them couldn’t take it anymore, there came the clearly audible click of a camera, sounding like an “amen” spoken in a new, digital language.

—Olga Tokarczuk, Flights (trans. Jennifer Croft)

When my partner and I met I was working as a routinely indolent clerk in our neighborhood used bookstore in Los Angeles. While I read through disarrayed stacks of vintage and out of print editions, he browsed the aisles, hiding sheets with typewritten passages from evocative texts or his own translations of favorite poems for me to find, on those rare occasions when I would get up from the desk to straighten untidy shelves. Over a decade later we have more or less traded places. The bookstore is gone, the shabby building demolished and replaced by empty looking luxury apartments. Now he does most of the bookselling, storing and stewarding the books at home, while I have taken over the role of mischievous typist. In other words, we have both become like bygone copies of each other.

He sometimes received a visit from his loyal friend Frank Harris—his future biographer—who, astonished by Wilde’s attitude of extreme laziness, would always make the same remark:

“I see you’re still not doing a stroke of work…”

One afternoon Wilde retorted:

“Industry is the root of all ugliness, but I haven’t stopped having ideas and, what’s more, I’ll sell you one if you like.”

For £50 that afternoon he sold Harris the outline and plot of a comedy which Harris rapidly wrote and equally quickly staged, with the title Mr. And Mrs. Daventry, at London’s Royalty Theater on 25 October 1900, scarcely a month before Wilde’s death in his poky little room at the Hotel d’Alsace in Paris.6

—Enrique Vila-Matas, Bartleby & Co. (trans. Jonathan Dunne)

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

readings

The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy (trans. Cathy Porter), Alma Books, 2009

Leah Bendavid-Val, Song Without Words: The Photographs & Diaries of Countess Sophia Tolstoy, National Geographic, 2007

Peter Finn and Petra Couvée, The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book, Penguin, 2015

Lewis Hyde, Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership, FSG, 2010

Borges wrote this story while recovering from a head injury, as a test to see if his narrative abilities had been affected by the severe septicemia caused when his head wound became infected. Satisfied with the result, the author would go on to write the rest of the stories published in his 1941 collection The Garden of Forking Paths.

See The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy (trans. Cathy Porter), Alma Books, 2009.

See Elif Batuman’s forensic investigation for Harper’s Magazine, “The Murder of Leo Tolstoy.”

See Rebecca Renner’s essay for Literary Hub, “The CIA Scheme that Brought Doctor Zhivago to the World,” and The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée.

Leo Tolstoy, in a letter to his son Ilya.

The play was a success and ran for 130 nights despite a week-long hiatus due to the death of Queen Victoria in January. During production Harris would discover that Wilde had previously sold the scenario rights to multiple parties who later contacted the playwright seeking large sums in royalties. The scandal over rights ownership would ultimately contribute to doubts about authorship: “Nine people out of ten believed that Oscar had written the play and that I had merely lent my name to the production in order to enable him, as a bankrupt, to receive the money from it.” See Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions by Frank Harris.

“To do what is forbidden always has its charms” - that’s a sentence you would follow anywhere…

very nice, thank you