on salt

discretion and detection

He thought his detective brain as good as the criminal’s, which was true. But he fully realized the disadvantage. ‘The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic,’ he said with a sour smile, and lifted his coffee cup to his lips slowly, and put it down very quickly. He had put salt in it.

—G. K. Chesterton, The Innocence of Father Brown

Ole Golly told me if I was going to be a writer I better write down everything, so I’m a spy that writes down everything.

—Louise Fitzhugh, Harriet the Spy

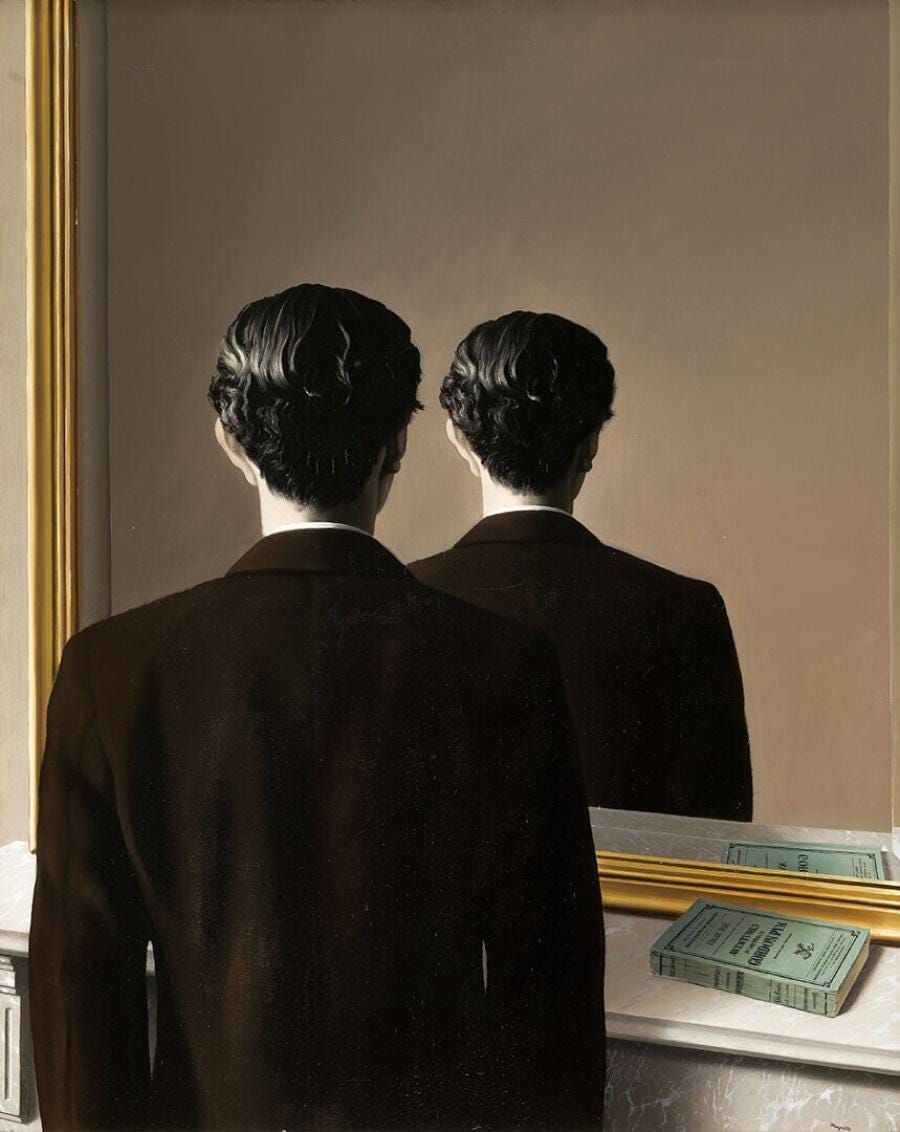

And then of course there is the investigative utility of the notebook, an item as emblematic as the magnifying glass and tobacco pipe. Columbo noting crime scene details in his inspector’s notepad. The amateur sleuth carting her composition book around with her everywhere. If she appears to herself at times the criminal, it’s because the notetaker moonlights as detective, is ever onto herself, a close tail, about to discover a break in the case. The independent scholar resembles no figure more than the private investigator, who likewise works outside the auspices of institutional authority, and no doubt faces the same disrepute among police officials as the unaffiliated researcher does with academics. Just as a private eye develops a filing system for cases solved and leads gone cold, the notetaker amasses her files too, organized to greater or lesser degrees, according to personal methods and codes. (The difference being that no one asks her to do this.) She shadows her subjects, leaves few pages unturned, pursues hunches, intuitively blending scientific with superstitious. No clue is too small, no offhand remark escapes her notice. And this is where the notetaker-as-detective comes nearest to apprehending the notetaker-as-criminal—because her single-minded pursuit necessarily verges on (that old hallmark of the deviant) obsession.

Moral tragedy—the tragedy, for instance, which gives such terrific meaning to the Gospel text: “If the salt have lost his flavor wherewith shall it be salted?”—that is the tragedy with which I am concerned.

—André Gide, The Counterfeiters (trans. Dorothy Bussy)

For most of her life Patricia Highsmith was known as the acclaimed crime novelist and author of bestselling psychological thrillers like Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley. Her uncredited second novel, published pseudonymously and her only work of fiction about an explicitly lesbian relationship, sold nearly one million copies before it was reissued under Highsmith’s name, 38 years after its release.1 The book had multiple aliases of its own over the course of composition and publication: after noticing a striking blonde shopper in a mink coat while working as a seasonal clerk in the Bloomingdale’s toy department, Highsmith feels the flush of a developing chickenpox infection and rushes home to transcribe in two feverish hours the plot of what she calls “The Bloomingdale Story;” her working title for later drafts is The Argument of Tantalus; she comes up with the title The Price of Salt while writing to her publisher in Munich; when it’s finally reissued under her real name, she opts to rename the novel Carol, after one of the main characters and the love interest of Therese, Highsmith’s alter ego.

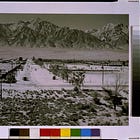

The Price of Salt was the first novel featuring lesbian characters that did not end tragically, and remained the only example of a happy ending in lesbian fiction for years after its release. The novel’s main characters begin an affair despite both being in committed relationships with men: Therese is engaged, Carol is married and has a young daughter. The affair is discovered when a private investigator hired by Carol’s husband follows them on a cross country road trip. The lovers separate, but Carol’s husband leverages the evidence of her homosexual affair to take full custody of their daughter, and Therese and Carol reunite in the end.

The chink in society’s armor might be found by a wretched act of mercy. An honest servant of the law might find himself caught between two crimes: the crime of mercy and the crime of duty.

—Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (trans. Norman Denny)

Highsmith’s first manuscript was more conventional, and ended with the separation of Carol and Therese. She rewrote the ending after a devastating falling out with Kathryn Hamill, an ex-lover on whom she’d partly based her character Carol. Shortly before finishing the final version she writes in her diary, “Oh, I write a book with a happy ending, but what happens when I find the right person?” Coward-McCann would publish The Price of Salt in 1952, after Harper initially rejected the manuscript. Highsmith learns it has been picked up during a trip to Salzburg with Ellen Hill, a new love interest with whom she’ll have a turbulent on-again off-again relationship, and whom she’ll catch snooping in her diary. Hill’s betrayal of privacy will lead Highsmith to abandon her diary for years. “Private thoughts were reduced and recorded in her notebook instead,”editor Anna von Planta explains, “her categories became more porous, her dates jumbled. Personal passages in the notebooks, along with sporadic diary entries, revealed moments of reflection, but no longer provided insight into the whole picture.”

In his 1822 philosophical treatise On Love, Stendhal develops the concept of “crystallization,” a process of idealization in the early stages of romantic love whereby “the mind discovers fresh perfections in its beloved at every turn of events.” He gives the origin of his theory of crystallization in an appendix detailing a trip to an Austrian salt mine near Salzburg. The French author is persuaded to visit the Hallein mine by Signora Gherardi, with whom he’s been summering in the Alps. While making preparations for their descent, they meet “a very fair and handsome officer of the Bavarian Light Horse” who becomes enamored with the Signora, praising her rapturously and even complimenting the pockmarks left on her hand from a bout of smallpox in childhood. “What struck me most,” Stendhal recalls, “was the increasing extravagance of the officer’s reflections; he was continually finding perfections in this woman which were quite invisible to me. Each thing he said depicted the woman he was beginning to love in a way less and less as she really was.” Still mystified by the officer’s sudden enchantment and searching for an adequate metaphor, Stendhal notices the Signora holding a twig encrusted with crystallized salt, a souvenir given to her by miners. By the time their party reaches the mine’s central cavern, “lit by a hundred lamps which became ten thousand as they were reflected by salt crystals from every side,” Stendhal’s newly hatched theory of crystallization has enthralled the imagination of his Italian travel companion.

They say I looked back out of curiosity. But I could have had other reasons.—Wisława Szymborska, “Lot’s Wife” (trans. Clare Cavanagh & Stanisław Barańczak)

The frame of my life is the frame of my work.2 Highsmith was often preoccupied with the interplay of art and life in her notebooks and diaries, where she kept a double account of her life: she logged more intense personal experiences in her diary, and used the notebooks as workbooks for writing and intellectual life, as well as exercise books for practicing foreign languages. Though Highsmith initially intended the two records to be wholly discrete from each other, as von Planta points out, “the lines blurred. Art and life couldn’t always be filed away into separate drawers. A veritable osmosis between the diary and notebook set in while Pat wrote The Price of Salt, because the experience entailed so much more than the act of writing.” Highsmith is aware of this blurring, and at times even seems to welcome it; as she observes in the notebook, “Writing, of course, is a substitute for the life I cannot live, am unable to live.” Planning a road trip to New Orleans with her friend Elizabeth Lyne, she writes in her diary on December 20, 1949: “I am very excited by the trip. Unavoidably, since Therese does the same thing with Carol. And I mean to keep my eyes, my heart open. I must feel everything, love everything, hear everything.” And the following year, also on December 20: “And of course these days I look for my Carol, Mrs. E. R. Senn, of Ridgewood, New Jersey. I look for her around Bloomingdale’s, though I should think it more likely that she shops at Saks oftener.”3

In the middle of the block, she opened the door of a coffee shop, but they were playing one of the songs she had heard with Carol everywhere, and she let the door close and walked on. The music lived, but the world was dead. And the song would die one day, she thought, but how would the world come back to life? How would its salt come back?

—Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt

My own mistake arose, naturally enough, through too careless, too inquisitive, and too impulsive a temperament.4 When Edgar Allen Poe effectively invented the detective genre in English language fiction with his 1841 short story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” the term detective had not yet entered popular usage.5 Poe referred to his crime fiction and mysteries as “tales of ratiocination.” In his 1844 “The Oblong Box,” Poe satirizes the heroic detective character he’d created in C. Auguste Dupin, making the unnamed narrator of his later tale jump to conclusions revealed by the end to be erroneous. On boarding a ship scheduled to sail from Charleston to New York, the narrator recognizes an artist friend’s name on the passenger list and, nosily comparing the number of guests in their party with the number of reserved staterooms, surmises that an extra room has been booked for the stowing of some precious cargo. When the pine box of the story’s title appears, “about six feet in length by two and a half in breadth,” the narrator considers its “peculiar” shape and, recalling a recent meeting between the artist and Nicolino, a mutual acquaintance and art collector, believes he’s deduced the hidden contents:

…and now here was a box, which, from its shape, COULD possibly contain nothing in the world but a copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper;6 and a copy of this very Last Supper, done by Rubini the younger, at Florence, I had known, for some time, to be in the possession of Nicolino. This point, therefore, I considered as sufficiently settled.

Sometimes all the information is there in the first five minutes, laid out for inspection. Then it goes away, gets suppressed as a matter of pragmatism. It’s too much to know a lot about strangers. But some don’t end up strangers. They end up closer, and you had your five minutes to see what they were really like and you missed it.

—Rachel Kushner, The Flamethrowers

When he hints through innuendo that he knows the box’s contents, the narrator is confounded by the artist’s hysterical reaction, but remains certain of his suppositions. The remainder of the ship’s passage is punctuated by odd behaviors among the artist’s party, strange circumstances, and inconsistencies observed by the narrator, until a change in weather causes the ship to wreck near Roanoke Island. Passengers and crew narrowly escape on a packed longboat with no room for baggage or cargo; as the lifeboat begins to launch, the inconsolable artist suddenly jumps back aboard the ship, and the survivors in the boat watch aghast as he ties himself with rope to the crate and pushes it into the sea, both plunging into the depths. In the aftermath of this shocking turn of events, the captain divulges that the artist’s wife had died tragically before the ship’s departure; in order to avoid a scandal arising from superstition, the widower had elected to transport the body discreetly, in an oblong box packed with salt.

Every book is perfect until one begins to write it.

—October 30, 1951, Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks 1941-1995

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

readings

Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt, or Carol, Norton, 2004

Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks 1941-1995, ed. Anna von Planta, Liveright, 2021

Andrew Wilson, Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith, Bloomsbury, 2021

Joan Schenkar, The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith, Picador, 2011

Stendhal, On Love, trans. Vyvyan Holland and C.K. Scott-Moncrieff, Liveright, 1967

Edgar Allen Poe, The Complete Stories, Everyman Library, 1993

—, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, Penguin Classics, 1999

She began writing her sophomore novel after coming out to her psychoanalyst, Dr. Rudolf Löwenstein. Highsmith records the visit on March 6, 1948 in her diary: “For the first time, I told a stranger that ‘I am a homosexual.’ And he listened to the story of my life. And said that my case will take about two years.” It would take her a little over two years to write The Price of Salt. See Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks 1941-1995, ed. Anna von Planta.

February 9, 1950, Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks 1941-1995.

Highsmith refers here to the blonde shopper who was her original inspiration for The Price of Salt. Like Therese, Highsmith visited the New Jersey home of Kathleen Senn after their encounter in Bloomingdale’s. “Today,” she confesses on June 30, 1950 in her diary, “feeling quite odd—like a murderer in a novel, I boarded the train for Ridgewood, New Jersey.”

Senn would commit suicide on October 30, 1951; she would never learn about the novel she’d inspired, and Highsmith never found out about Senn’s suicide. See Andrew Wilson’s biography, Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith.

Edgar Allen Poe, “The Oblong Box.”

The first American police detective agency would form in Boston in 1846; famed Pinkerton National Detective Agency began in Chicago as Pinkerton & Co. in 1850.

In Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Judas leans back conspiratorially, his elbow propped on the table where he has overturned the salt cellar, spilling salt over the tablecloth—a visual omen portending his imminent betrayal.

To even make the claim that the salt in that saltshaker is white—that implies that you had at least some conception of the fact that darker things exist. You’re comparing the hue of that salt to the conglomeration of all the hues of everything that you’ve ever seen in your conscious experience in your life. And that goes for bitterness. That goes for hardness. It goes with everything. - Stephen West