on sycamores

sarcomas and cicadas

All kinds of smoke: the blue, light smoke, the white, the gray, the heavy black, all go up to the azure and are lost, and the azure remains. (1905)

There are landscapes that die like people one loves. (1906)

—The Journal of Jules Renard

I’ve been thinking about the sycamore in Sullivan canyon. Wondering if it’s still living since the fire. Giant and sprawling, a hundred years old or more I’d guess, it was home to an established bee colony whose wax combs were on display, viewable through a small hollow in its trunk, like a miniature art gallery. Bees are artful. They communicate through little dances they put on for each other. They select the most vibrant, attractive flowers to pollinate, dabbing their fluffy legs, abdomens, and antennae like paintbrushes in pollen and sprinkling their favorite colors across their canvas of a landscape.

In a letter to Reverend John Trusler in August of 1799, William Blake defends his artistic and spiritual independence against criticisms made by the priest and enterprising self-help author, who had commissioned Blake to illustrate printed sermons he planned to sell at an immodest profit. “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way,” Blake lectures. “To the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.”

The sycamore grew near an intermittent creek that has run dry more years than not lately, when the canyon isn’t flooded by winter storms during El Niño events. With few exceptions, I’ve visited it every week for nearly ten years. A remarkable consistency when I consider how it began with a purely accidental encounter.

“All actual life is encounter,” says Martin Buber. And, “relation is mutual.” To illustrate this he gives an example of how he can view a tree as object: separate and merely measurable. Or, “if I have both will and grace,” as another being bound up in relation with himself. “The tree is no impression, no play of my imagination, no value depending on my mood; but it is bodied over against me and has to do with me, as I with it — only in a different way.” By stepping into this mutual relationship, he argues, we allow ourselves to become fully human.

I was walking Brody, a Bernese mountain dog, down the street from his apartment at Palisades Park, where I met an older married couple with a standard grey poodle. When the wife asked if I went hiking I was mildly surprised. I’d just started hiking regularly, I told her, at a local trail in Sullivan Canyon. (In fact I’d found the trailhead by taking a wrong turn into a dead end residential road.) Without hesitation she explained that she had been diagnosed with cancer and was starting treatment that made her less active than she’d once been. They were newly in need of help giving their energetic poodle regular exercise. The husband quietly shifted his feet, looked out at the horizon beyond the fragile, exposed bluffs. “I’m Naomi, by the way. This is Michael, and that’s Romy,” she nodded at the poodle, who cocked her head and looked up at us.

They drive from farm to farm, between last year’s blights and next year’s vanishing topsoil. He shows her extraordinary things: the spreading cambium of a sycamore that swallowed up the crossbar of an old Schwinn someone left leaning against it decades ago. Two elms that draped their arms around each other and became one tree.

This scene appears early in Richard Powers’ The Overstory, a novel in which nine otherwise unrelated characters become intertwined through their personal relationships with trees.

Cambium is a botanical term that comes from medieval Latin. Meaning “change or exchange,” it was originally a medical term for one of the humors believed to nourish the human body.

I’ve thought back on that meeting many times. As Naomi’s cancer entered partial remission, then returned and gradually worsened, and ultimately caused her death on January 20, 2022, after a long period of painful illness in the thick of the Covid pandemic. After Romy succumbed to an epileptic seizure six months later. I’ve wondered what prompted her trust in me, why we connected so easily, what confluence of choice and chance led to our long and pivotal relationship revolving around care – my care for their dog, their care for her through chronic illness. Pivotal for me, because I began to learn about grief when I met Naomi, at the same time that I began to notice so much life hiking along the creek bed with Romy and other joyful dogs each week, year after year.

Inosculation, the natural phenomenon whereby the trunks, branches or roots of two trees fuse together, derives its name from the Latin roots in + osculatus, meaning to kiss or embrace inward/into/against. In forestry, inosculated trees are referred to as gemels, from the Latin for twin or pair.

In August 2023, for the first time in its history, the National Hurricane Center issued a tropical storm warning for Southern California. Hurricane Hilary washed out much of the dirt maintenance road that had followed the creek since the 1930s, and the trail has since remained closed for repairs. I’ve been unable to visit the sycamore in the intervening months. Though I have thought of it, periodically, like a friend I’ve been meaning to call who lives in another city.

Annie Dillard records her pilgrimages to an old sycamore near a creek in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Like many sycamores, it is “quirky, given to flights and excursions.” She explains that she comes to the shaded creek not for “sky unmediated, but for shelter.” She traces the sycamore’s growth as a member of its natural environment, and a figure in the human imagination from ancient history through the present. She relates an anecdote from Herodotus in which the Persian King Xerxes happens on an eastern plane tree—cousin of the American sycamore—so grand he ornaments it with gold and stations an elite soldier to guard it. She paraphrases her friend, the poet Rosanne Coggeshall, as deeming “sycamore,” perhaps idiosyncratically, “the most intrinsically beautiful word in English.” “Big trees stir memories,” Dillard reflects. And wonders, “What if I fell in a forest: Would a tree hear?”

Naomi and I are standing in her living room. I’ve just dropped off Romy from a hike and we are coordinating schedules for her upcoming treatments, which will include blood transfusions, and a bone graft. I tell her about my surgery, which required transplanting tissue from the curved ridge of my pelvic bone to my broken left clavicle. (I don’t tell her about calling my surgeon in the middle of the night after the procedure because I could barely walk to the bathroom and thought something must be wrong. Or that it was the most painful aspect of the entire ordeal. More painful than being struck by a car and breaking my clavicle.)

Sarcoma is an ancient word. In both Latin and Greek it meant “excrescence of flesh”. The original form comes from a Proto-Indo-European noun derivative of the verb “to cut”. Growth and severance, symptom and prescription—twinned senses, each redoubling the other.

She’s excited to talk to someone with firsthand experience, and I want to give her that kind of empathy, to be a compassionate witness. We discuss the crude method and anachronistic tools modern surgeons use to chip off fragments of bone from one part of the body and graft them onto another. “It’s basically a chisel,” I say. “I know! I’ve been looking at videos online. Here, do you want to see?” She extends her phone screen towards me. I draw in a short breath and hold it. I can’t look. “I’m sorry, I don’t know why I asked you that,” she apologizes. “No, really, it’s fine. I’m not usually squeamish about things like that.” The room is quiet with our shared apprehension: there are places we each go unaccompanied, adrift, in the sodden lumber of the body.

Other rites belong to those confined in the sodden lumber of the body. — The Fragments of Heraclitus

“The catalogue of trees.” In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Orpheus emerges from the underworld without Eurydice—like Lot having broken his promise not to look back—and finds an open hilltop. Playing his lyre, he summons many shade trees cataloged by Ovid. Some have epithets: sacred oaks, soft linden, tender hazel, useful ash, supple palm, genial plane tree. Last in his list is the cypress, followed by a short digression on the myth of Cyparissus, who unwittingly kills a beloved tame stag and surrenders so entirely to his grief that he is transformed into a cypress tree. From then on, Ovid reports, the cypress was a symbol of grief.

Some animals I’ve encountered in the Santa Monica Mountains: green parrots, ravens, hawks, turkey vultures, mourning doves, woodpeckers, songbirds, coyotes, rabbits, ground squirrels, lizards, skinks, rattlesnakes, gopher snakes, California kingsnakes, annual cicadas1, bees, earthworms, caterpillars, orb weaver spiders, praying mantises, a tarantula, a dead shrew mole.

David Lynch’s father, Donald Lynch, was a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture and the U.S Forest Service. He studied trees, and insects. He met Lynch’s mother Edwina while on a walk in the woods, and made an impression by holding a low-hanging branch for her as she passed.

David was born on January 20, 1946. He died five days before his 79th birthday, from complications of emphysema following a mandatory wildfire evacuation from his home in the Hollywood Hills.2

I’ve often gone to Sullivan Canyon for shelter. Broad sycamore leaves provide ample shade from sun in summer. Sycamores tend to be late to leaf in spring and early to shed in fall, giving an abbreviated break from peak summertime temperatures followed by a thick carpet of autumn duff. Neighboring oaks make improvised cover during spring or winter rain spells. The canyon is monastic, cloistered by arching tree limbs and a hush of papery sycamore leaves disrupted sporadically by brash, unseen flocks of green parrots passing over.

In one of his Nature Stories, Jules Renard’s narrator crosses a sunburnt plain to a grove of trees growing near a spring “known only to the birds.” He is so at home among them, he feels they must be his real family, and says he will soon forget his human family, and become adopted by the trees. The fable ends with a list of what he is learning in order to deserve his tree family: how to watch the clouds passing, how to be still, how to stop talking.

Above Sullivan Canyon run two foothill ridges with popular hiking and biking trails that double as fire roads in emergencies. In exchange for sometimes harsh exposure to sun and wind, they give expansive views of the bay and city. On clear days you can see downtown Los Angeles and Catalina Island from the same vantage. Looking down on the canyon below you will glimpse a narrow grove of sycamore trees whose canopy veils the creek, protecting it from view, and giving it away. A poorly kept secret.

Trees have long thoughts, long-breathing and restful, just as they have longer lives than ours. They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them.

—Wandering: Notes and Sketches by Hermann Hesse

Sycamores are long-lived. There used to be a custom of planting two sycamores, called “bride and groom” trees, to celebrate a marriage. A towering groom tree, believed to have been a present to Simeon Strong and Sarah Wright for their wedding on January 12, 1763, still stands outside the Strong House, now the Amherst Historical Society Museum. Emily Dickinson attended Amherst Academy across the street in the 1840s, from age seven to fifteen. She would have seen the marital trees in their prime. The sycamores were older than the town itself, and would have been saplings when Amherst was chartered in 1759. The bride tree was removed in 1957 after extensive damage from storms left it a hazard to maintain.

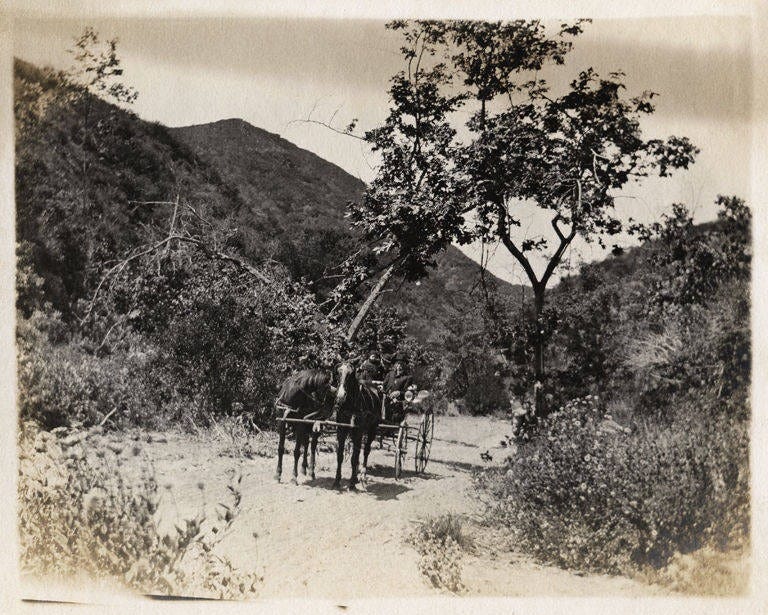

*A selection of photos and videos I’ve taken over the years in the Santa Monica Mountains is viewable here.

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

“A hot-weather sign,” E. B. White called the asterisk. “The cicada of the typewriter.” The periodical brood is an alluring metaphor. He composes a vignette on its life cycle:

At eight of a hot morning, the cicada speaks his first piece. He says of the world: heat. At eleven of the same day, still singing, he has not changed his note but has enlarged his theme. He says of the morning: love. In the sultry middle of the afternoon, when the sadness of love and of heat has shaken him, his symphonic soul goes into the great movement and he says: death. But the thing isn't over. After supper he weaves heat, love, death into a final stanza, subtler and less brassy than the others. He has one last heroic monosyllable at his command. Life, he says, reminiscing. Life.

I recently learned (through Miranda July’s newsletter) that the David Lynch Foundation provides scholarships for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault to take the Transcendental Meditation course for free. A link to fill out the form is on the website.