on quarries

quixotes and alcaldes

You never know how the past will turn out.

—I’m Not There, dir. Todd Haynes

An impulse toward note taking grows from an anxiety about loss. The loss of ideas, insight, phrasing, novelty. The loss of something forgotten, a passage of lived moment into lapsed memory. It is that documentarian urge to record everything and find the truth later, in the edit. A hoarding of personal experience. Notes have the arrested quality of photographs, preserved and self-contained, set in an album of other discontinuous moments. What grows from the collection of notes over a lifetime is a sense of interconnectivity, and indeterminacy. Each notebook contains its particular miscellany. The notes themselves sit in uneasy proximity to each other. There are harmonies, and there are discordances between them. This may be the whole point: that nothing resolves, finally, into crafted narrative. The stridency of composition is mercifully deferred, stays in the future tense. The past is continually offered up to interpretation, and re-interpretation, by the present.

In every collector hides an allegorist, and in every allegorist a collector.

—Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

George Eliot famously called her notebooks “quarries”, the most well known being the Quarry for Middlemarch. Half of its contents consist of meticulous notes on the leading medical science of the period. The other half is dedicated to the structure of the novel, with a few pages on England’s first Reform Bill of 1832. The novel is set forty years prior to its publication, during a period of political and medical reforms coincidental with the second cholera pandemic that reached England in October of 1831. Middlemarch is a fictional English town placed in a real time in the past. The reader of Middlemarch revisits familiar events in an invented domain, and must blend novelty and history, quixotically, in her imagination. Eliot imagines her notebooks as sites she returns to, again and again, to mine the raw materials out of which she builds fabled worlds. Quarry for Middlemarch is a small black leather notebook, a little over four by six inches in size, and relatively thin. It could slip easily into a pocket.

But in any rational criticism of the time which is meant to guide a practical reform, it is idle to insist that action ought to be this or that, without considering how far the outward conditions of such change are present, even supposing the inward disposition towards it. Practically, we must be satisfied to aim at something short of perfection—and at something very much further off it in one case than in another.

—George Eliot, Leaves from a Notebook

The first time I heard the word quarry was in middle school. Every morning I would ride the bus from our stop outside Mal’s Market in Seaside to Walter Colton Middle School. The school was set among pines on a hill above Monterey’s historic Colton Hall. We had been instructed by school authorities not to trespass in the adjacent quarry, which was a dangerous place for adolescents. Any students caught there would face automatic suspension. Most of us were unaware of the existence of the quarry until we were warned against exploring it. When our bus approached a gully near the school entrance the next day, someone yelled, “It’s the quarry!” We looked out the windows of the right side of the bus like tourists at an abrupt wooded drop beyond the guardrail bordering the road.1 The sight didn’t match whatever I’d had in mind, some combination of scenes from adventure movies featuring lost treasure, mines or archeological digs—Jurassic Park and Indiana Jones, but more so personal favorites starring child actors like Stian Smestad in Shipwrecked, or Christina Ricci and Anna Chlumsky in Gold Diggers: The Secret of Bear Mountain. I tried to imagine a quarry, conjuring piles of boulders, rocky crevasses, mine shafts, abandoned equipment, interrupted excavations. The noisy bus fell quiet as we drove past a gap that remained a mystery to us.

The first development of stone resources recorded in California after the Gold Rush were granite quarries at Folsom, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The largest producer of granite was Folsom State Prison, which operated for nearly a century and supplied granite for the prison’s walls, Folsom Dam, and for the foundation of the state capitol building, all produced using prison labor.

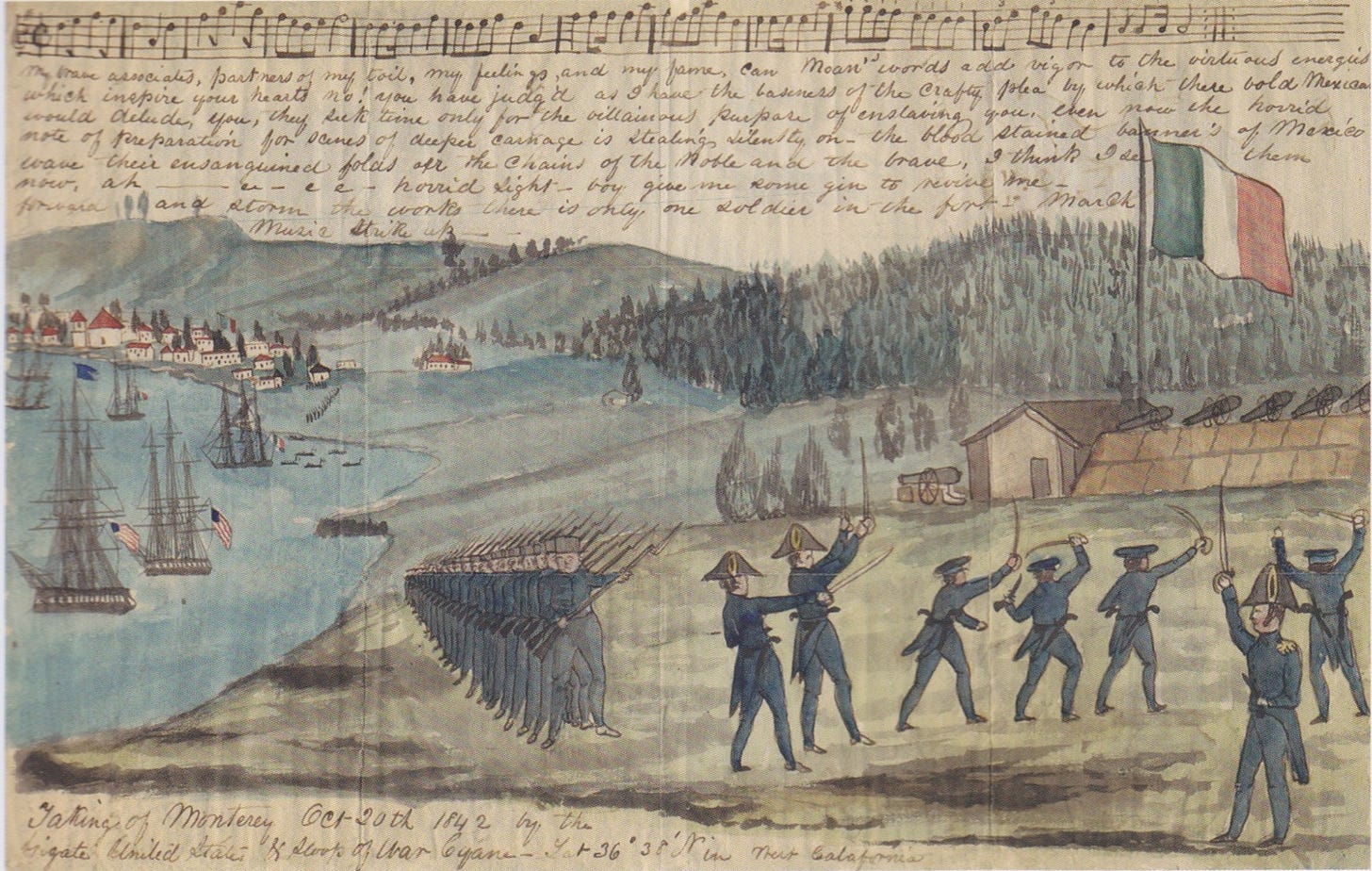

Walter Colton was a chaplain and writer from Vermont who became Monterey’s first alcalde. He served as mayor, judge, sheriff, coroner, prosecutor, and tax collector, as well as co-publishing the state’s first newspaper, The Californian, with Robert B. Semple. Colton organized the construction of Colton Hall at virtually no cost, quarrying Monterey shale from neighboring hills with convict labor, and raising what funds were needed through town lot sales, gambling fines and taxes on local cantinas and liquor stores. If he crossed paths with a local delinquent he might arrest and jail them, judge their case and sentence them to labor on his namesake Hall. When it was finished in 1849, he praised the Greek Revival building as unrivaled in California, and admired its blocks of fissile, chalk white stone, “which easily takes the shape you desire.” In September and October that same year, California’s first Constitutional Convention would be held at the newly constructed town hall. Delegates would debate at length whether California should enter the Union a free state, ultimately electing to ban slavery—except as punishment for a crime—in the state’s original constitution. Five years later a new jail adjacent to Colton Hall was finished, and would continue to be in operation for over a century.

The scheme was regarded with incredulity by many, but the building is finished, and the citizens have assembled in it and christened it after my name, which will now go down to posterity with the odor of gamblers, convicts, and tipplers. I leave it as humble evidence of what may be accomplished by rigidly adhering to one purpose, and shrinking from no personal efforts necessary to its achievement.

—Walter Colton, Three Years in California

The office of alcalde was a Spanish judicial and administrative position, analogous to a municipal magistrate, that arose in the Iberian Peninsula during the medieval holy wars known as the Reconquista. The title was borrowed from the Arabic al qadi, meaning “the judge”.

Throughout his life, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was at turns valiant and deviant. A 19th century biographer discovered an arrest warrant issued for Cervantes in Madrid on September 15, 1569, charging him with wounding Antonio de Sigura in a duel—an event believed to have prompted his family’s sudden relocation to Rome. After receiving a military commission through a family friend in Naples, Cervantes and his brother sailed with the Spanish Holy League on the Marquesa, and took part in the pivotal Battle of Lepanto on October 7, 1571. The Spanish vanquished the Ottoman fleet, and in the course of fighting Cervantes sustained gunshot wounds to his ribs and left shoulder, leaving his left hand paralyzed and earning him the nickname, “The One-Armed Man of Lepanto”. A few years later the brothers would be taken captive by Barbary corsairs and held for ransom in Algiers. His family only able to afford one ransom, Cervantes gallantly remained a captive and his brother was released. The author stayed in captivity for five years, was sold and re-sold as a slave laborer, at one point being transported to Istanbul, where it’s speculated that he worked on construction of the Kilic Ali Pasha Mosque complex.

The poet Robinson Jeffers built Tor House and Hawk Tower, where he would write all of his major works, at Carmel Point. The likelihood of war in Europe combined with the death of his father in 1914, and the inheritance of a sizable annuity, led Jeffers and his wife Una to seek property in the nascent coastal village. Tor House was finished with the help of a contractor in 1920. Four years later Jeffers completed work on Hawk Tower alone. Inspired by Tudor stone masonry and prominent geological formations found on English moors, Jeffers designed both cottage and turret to be almost entirely stonework. Granite boulders for the facade of the home were hauled up from the beach below using horses and heavy rope.

After four failed escape attempts, Cervantes was finally freed by the Trinitarians, an order of the Catholic Church dedicated to ransoming Christian captives. He would go on to work as a Spanish spy in Portugal and Oran, then as a civil servant and tax collector—in 1597 he was indicted and briefly jailed for malfeasance—in addition to writing the first, and perhaps greatest, modern novel. In 2015, archeologists exhumed remains in a wooden coffin etched with the initials “M.C.” from beneath the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians in Madrid. Even before DNA verification, the bones were quickly identified by visible bullet wounds on the ribs, and a crippled left arm.

Never be astonished, dear. Expect change, Nothing is strange. —Robinson Jeffers, “For Una”

In Don Quixote, the eponymous knight errant convinces the farm laborer Sancho Panza to become his squire by promising him a small governorship of some isle, and improbably delivers on that promise near the end of their picaresque history. Also improbably, Panza reveals himself to be a wise and practical ruler of the fabricated Ínsula Barataria, given to him as a prank by a mischievous Duke and Duchess. A series of legal cases are brought before Panza which he solves as if they were riddles.2 Patrolling the hamlet, he mediates a gambling dispute, arrests a suspicious person who narrowly escapes jail through a bit of sophistry, and philosophizes on the demands of governing. The steward accompanying him, impressed with Panza’s eloquence, remarks, “every day we see something new in this world; jokes become realities, and the jokers find the tables turned upon them.”3 After ten days of increasingly humiliating tricks, Panza wearies of his faux governorship and resigns. He leaves to give his account to the Duke, and finds himself still on the road to the nobleman’s castle after dark. He and his donkey stumble into a pit on the side of the road—a parody of Don Quixote’s earlier adventure in the Cave of Montesinos—where they are trapped until morning, when Don Quixote happens by and comes to their rescue. With thick rope and the considerable work of many villagers, the pair are raised out of the cave. Panza regrets this undignified conclusion to his brief stint at governing, and characteristically recites a string of adages, some familiar, as “man proposes and God disposes,” and others—“time changes the rhyme”—less so.

You know, the worst ain't so bad when it finally happens. Not half as bad as you figure it'll be before it's happened.

—Treasure of the Sierra Madre, dir. John Huston

When it’s over you know you’ve seen something.

—Pauline Kael on Treasure of the Sierra Madre

If you enjoyed this post you might like...

In fact the quarry is located to the north, on the other side of the school, in a much deeper pit.

One case, borrowing from hagiography in The Golden Legend, is resolved when Panza prophetically uncovers a stash of gold escudos hidden inside a defendant’s cane.

This phrasing comes from John Ormsby’s translation of the novel; Edith Grossman’s translation is slightly less playful: “deceptions become the truth, and deceivers find themselves deceived.”

I see a wonderful book here. Notes on Notes. Keep noting!